Blackouts v. Boys Weekend

The 2024 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among 16 of the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 7 • OPENING ROUND

Blackouts

v. Boys Weekend

Judged by Leah Schnelbach

Leah Schnelbach (they/them!) is the features editor for Tor.com and a fiction editor for No Tokens. Their fiction, nonfiction, and interviews have appeared in The Rumpus, Joyland, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, and Electric Literature, among other estimable places. Turn-ons include Cate Blanchett’s Ocean’s 8 wardrobe, good espresso, and exhaustively researched oral histories of obscure topics; turn-offs include the phrase “elevated horror,” unnecessary prequels, and the death of the author. Known connections to this year’s contenders: “Chris Bachelder was one of my instructors at Sewanee Writers’ Conference and I’ve edited Henry Hoke's work for Tor.com.” / @cloudy_vision

A billion years ago, when I was about 14, I took a bus to the Good Library. Unlike my Actual Local Library (three small rooms and a furious, elderly librarian who removed sex-ed books from the shelves as fast as they went up) or the Next Closest Library (dark and weird with nothing more recent than the 1970s), the Good Library was three stories tall, with large plate-glass windows, squashy chairs, a labyrinth of shelves, and thousands upon thousands of books.

It was in the Good Library that I found a battered copy of Martin Duberman’s About Time, and it was in About Time that I started learning queer history. Or should I say, what of queer history could be patchworked back together by the people who survived the 20th century. It was a revelatory day that’s stayed with me as one of the great reading experiences of my life.

Maybe this is a weird opening for this essay, but I want to illustrate why I felt such overwhelming gratitude for the two books I got to read for this year’s Tournament: Boys Weekend by Mattie Lubchansky, and Blackouts by Justin Torres. I’ll start by saying that reading these two books brought me a lot of joy.

In fact, I’m going to tell you up front that I am sidestepping the requirements of the Tournament. I try to live my life in a spirit of “what about…both? Both is good.” Why should my reading life be any different? Here in paragraph four I say to you: While there can be only one, and I found myself pulling for Blackouts slightly more than Boys Weekend, I recommend them both to you. Maybe my reaction is stronger because I read these two books as a conversation? I’m going to try to untangle why I was so moved by both of them as we go, before delivering my (reluctant!) verdict.

In Boys Weekend, Sammie is a trans artist in near-future, somewhat-dystopian Brooklyn, happily out and very left-wing, with a partner and a large queer intentional family. But they’ve been asked to serve as “Best Man” for their old college buddy, Adam, who is part of an old life and an old crew (the Beer Boyz) who are aggressively heteronormative. They said yes for the sake of the friendship, but now they have to be part of the bachelor party weekend on El Campo, a remote, man-made island in lawless international waters—a floating hyper-Las Vegas where you can take any drugs you want and a battalion of clones clean up after you.

The weekend gets more awkward as the hours click by—none of the boys have much interest in hearing about Sammie’s life. Boys Weekend illustrates the gap between them in a lot of ways: photos on Sammie’s fridge show the college friends’ buttoned-up wedding and birth announcements next to a shot of Sammie at Pride with heavily tattooed people in bikinis and mesh shirts. The former Beer Boyz, Adam, Farhad, and Parker, are joined by Dan K, Dan H, Fred, Erin, and Kris. The rest of the group are all in tech and/or finance—except for Kris, who’s a cop—and have no qualms about spending buckets of money on strip clubs (with clone sex workers) and extreme hunting games (you get to hunt clones). They constantly misgender Sammie, and in a drumbeat of casual misogyny, only talk about their wives back home to complain about them. In the background of all the emotional jockeying, Sammie notices what seems to be a cult scoping them out—and what might be a sea monster in the water.

Boys Weekend captures the awkwardness of these exchanges so well that it made me glad when the real horror part of the book kicked in.

And then there’s Erin. A co-worker of one of the former Beer Boyz, Erin might be my favorite aspect of the book—a straight cis woman who just wants to be one of the guys, and is openly hostile toward, and disgusted by, Sammie’s decision to step outside of the gender binary. This comes to the fore when they’re paired for a “dangergame” of hunting clones of themselves. All of Erin’s resentments about being treated as “lesser” boil over in a few panels (Boys Weekend is a graphic novel) of her rebuffing Sammie’s attempts to bond with her over being the only “femmes” on the trip. Erin can’t understand how Sammie can reject all the male privilege that she so desperately wants. Meanwhile, Sammie is having a meltdown over the idea that it’s fun, somehow, to murder a version of yourself. The scene encapsulates a lot of what works so well in Boys Weekend: dark humor and pointed social observation that suddenly tips into an emotional bloodbath.

As Boys Weekend is a graphic novel, quoting doesn’t quite do it justice, but I want to give you a sense of the book’s fabulous skin-crawling humor. At one point Farhad is alone with Sammie long enough to monologize at them for a few panels:

Farhad: “Looks like we’re a few minutes early! Who was on the phone? Wife?”

Sammie: “Yeah, we—”

Farhad: “—you know, I’ve been meaning to ask… [he closes his eyes, and presses a hand to his chest] So. I wanna do all this stuff right. You know, I’m an ally. And, like, since you. Whatever, came out? You say came out, right, even if it’s not like, for gay? For gender? Anyway, what do you and—Maya?”

Sammie: “…Mia.”

Farhad: “Right. What do you guys do for, like, sex. Now. Because she wanted to marry a man, right? (Farhad puts a hand on Sammie’s shoulder) You know, because I just want to get this all right.”

Sammie: “Because you’re an ally.”

Farhad: “Exactly!”

Boys Weekend captures the awkwardness of these exchanges so well that it made me glad when the real horror part of the book kicked in.

In Justin Torres’s Blackouts, an unnamed narrator leaves their city and travels into the desert to find Juan, an acquaintance from years earlier. Juan is living in a place called the Palace—except Juan is dying more than living, and the Palace is a decrepit old sanatorium. Our narrator, lovingly called “Nene” by Juan, tends to Juan’s old friend, and the two share stories. “Juan was dying, but only in the light, and only in the body. In the dark, his voice filled the room, sharper and more alive than I.”

Juan tells Nene about a book called Sex Variants: A Study of Homosexual Patterns, a case study of queer lives and practices published in 1948. (This was a real book, credited to Dr. George W. Henry, and if you look through it, you’ll see that the interviewees’ stories are crowded and drowned out by horrific medical commentary.) As Juan walks Nene through the history of the book, he tells him about Jan Gay, a lesbian writer and activist who gathered stories from queer people after working with Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld. But Dr. Henry and the committee of psychologists and doctors took the studies she and her queer collaborator, Thomas Painter, compiled, for their own purposes. “The point is the committee didn’t want its findings to be tainted by Thomas’ theories, or Jan’s activist approach to documenting lesbian lives. The committee’s focus was pathology, mixing the newish Freudian psychosexual theories with physiological explanations for deviance. Eugenics.”

FROM OUR SPONSOR

In exchange for these history lessons, Nene tells Juan about the crooked path that brought him to the desert, especially his various misadventures as a vibrant young sex worker. But immediately twists appear: Someone has gone over Juan’s copy of Sex Variants with black marker, wrenching beautiful, celebratory erasure poetry from those long-dead doctors’ homophobia; Nene’s stories are nebulous and shifty, and punctured with accounts of the blackouts that plague him. How much of what these two men are sharing with each other is “true?”

So, you see I got lucky here, yes? These two books pair uncannily well.

They’re both multilayered horror—one the horror of being trapped in an isolated place with people whom you can’t trust, which gradually shades into a more cosmic horror. Is it worse to be faced with a wall of tech bros, all wearing matching, branded vests, staring at you in a classic mix of disgust and incomprehension? Or a writhing mass of eldritch tentacles that want to eat you?

At least the writhing tentacles are cool.

In Blackouts, the threat is less supernatural but just as cosmic: How do you carry yourself into the future when your past has been erased? How, as a young queer person, can you have any sense of belonging, community, future, anything, when people who didn’t understand your kind 70 years ago have systematically destroyed all the records? When part of what makes you you is seen as a disease?

The scene I most want to quote, I’ll stay away from, only because I don’t want to rob any of you of the experience of reading it. I was tumbling forward through the book when I came to a breathtaking moment of reckoning—only to reach the bottom of the page and realize that this, now, was the end of the book. A perfect work of structure, to give us a deathbed conversation that feels so slow at times, and then to pull us up short when the words stop and leave us wishing for another five minutes of talk. Instead, here’s a scene of Juan and Nene meeting, years before the events in the desert:

Such a gentle old man. Later, I would learn all manner of vocabulary to think about sex, and gender, but invoking any of those words would be anachronistic—I was a teenager from bumfuck nowhere; I saw only that Juan transcended what I thought I knew about sissies. When he spoke, he spoke in allusion, literally, often pausing to check, with a look, whether I followed. I don’t think he expected me to understand directly, but rather wanted me to understand how little I knew about myself, that I was missing out on something grand: a subversive, variant culture; an inheritance.

And indeed, Juan speaks in quotes and allusions to literature, theater, and film—educating his young friend even as he himself delights in remembering the language, and in many cases the coded queerness, of the works that have sustained him through his life.

Both books also play with metanarrative. In Boys Weekend the mashup is between comics, specifically the aesthetic and tone of early-’00s webcomics like Goats, Achewood, and Venus Envy, cosmic horror, and a deeply personal narrative about identity. Blackouts finds its energy in a double-Scheherazade idea, two people telling each other stories to stay alive. There is an element of the confessional (in both the Catholic and reality-TV sense), of whispering your secrets in a closed space for an unseen audience. There’s the original text of Sex Variants, compiled by Jan Gay, the text created from her work by Dr. Henry, and that text redacted and turned into erasure poetry. Then there’s a description of the film that Juan wants to make about Jan’s life, oral history traded by the men, doubling and mirroring, names that echo each other—Juan’s full name is Juan Gay, a mirror to Jan Gay, which was the nom de queer of a real person, Helen Reitman, who really did all that work and had it stolen from her by homophobic doctors.

It gave me the thing I look for in fiction, the sense of absorption and lost time.

Visually the books compare in interesting ways as well. Boys Weekend is a graphic novel. The text and images play together, comment on each other, and build to a very different reading experience than that of reading straight (sorry) prose. But Blackouts, too, includes pages and pages of erasure poetry, and also illustrations from children’s books written by Zhenya Gay, Jan Gay’s partner, photos included in Sex Variants, a still from Orson Welles’s Voodoo Macbeth, and photos that purport to be of Juan Gay and Nene themselves. (I say “purport” because who even knows what’s “real?”)

Boys Weekend is Sammie’s story. We see everything through their POV, and the most arresting section of the book is about their own confrontation with themself. Because the bros are treated as a WALL OF BROS, it was a little difficult for me to invest in the moments when Sammie was trying to have a more intimate relationship with Adam. I didn’t get a sense that Adam was different enough to justify Sammie’s attempts, and there were points when I just got annoyed with Sammie for going at all (though I’ll admit, there might be some “physician, heal thyself” stuff going on there), but I do think the book would have been served by a stronger sense of lost friendship between the two of them.

Juan and Nene both come to such vibrant life that they’ve been in my head since I finished the novel. It’s a bit easier for Nene because the story is unrolling in his voice, but I saw Juan through his eyes, but also felt like I had a sense of who Juan was on his own, before Nene had known him, when Nene wasn’t in the room. Juan-via-Nene is a very compelling storyteller, and easily sweeps through decades of history in a really captivating way.

I realize I might be making Blackouts sound like a purely academic exercise, but it’s also a gripping love story more than anything else. It gave me the thing I look for in fiction, the sense of absorption and lost time. Since I finished the books, and began thinking about how to write about them for the Tournament, I kept asking myself how they made me feel. I mentioned the gratitude up at the top, but that’s different. The two books read very differently—and I don’t mean just because one is a graphic novel and the other more prose-heavy. Boys Weekend is fun—a blast of pure anarchy, moments of gross-out humor, and dark jokes. I read it fairly quickly. Blackouts took me a bit longer, and is definitely the heavier experience. There is so much pain in the pages, without any of the distance provided by sci-fi or horror. It’s an extremely rewarding read, but it required more breaks.

Boys Weekend was one groan of identification after another for me. I’ve spent a lot of time around heteronormative Americans over the years, and a lot of time around People of Tech, and every interminable dinner as Sammie sits there in silence listening to the guys bitch about their wives, or compare passive income strategies, felt terribly familiar. Blackouts, meanwhile, made me feel claustrophobic, like I was choking on dust. (In a good way.)

Having said that, while I loved Lubchansky’s gleeful slalom through horror, I did wish they’d left us sitting with the clone idea a little longer. Those were rich scenes, and I wanted Sammie to have to contend with their clone and thoughts about identity even longer. Because the book is frenetic, before you know it there’s cult activity and eldritch monsters to deal with—but I found myself thinking back to the scenes at the Dangergame Clone Hunt. On the other hand, I also wanted even more violence, more splash pages of El Campo visitors being torn asunder—basically, I wanted the book to take its turn to horror sooner than it did. What is there is fantastic, but I think I wanted to be as immersed in Sammie’s shock at the story’s turn, as I was in their discomfort with the rest of the bachelor party trappings.

In Blackouts, there was sometimes a sensation of freefall as names and facts and historical records piled up. Were any of these people real? Were they all real? Where were the lines? Ultimately, I decided it didn’t matter, that I needed to let the information overwhelm me rather than look things up and break the spell—but the breathlessness is part of the reading experience. The book gave me a sense of walking through dark rooms, feeling ahead for familiar shapes, like turning the next corner would give me an answer. But of course, part of the point of the book, for me, was that we have to make our own answers.

As I said up at the top, read both! I think you should give both as gifts to any young queer people you know! Be the gay uncle you wish to see in the world! But having said that, I’m advancing Blackouts. Justin Torres has created a rich, transcendent fiction, as well as a great work of queer history.

Advancing:

Blackouts

Match Commentary

with Meave Gallagher and Alana Mohamed

Meave Gallagher: And here we are, our first commentary for the 2024 Tournament of Books. Welcome back, Alana! How’s your year been?

Alana Mohamed: Hello, Meave—and thank you for having me back! The year has been strongly OK, despite the terrors that surround us; they offer a certain clarity. I’m reading more books and doing more mutual aid work—and (talking about) working less. How are you?

Meave: I’ve been spending a fair amount of time yelling at my elected representatives, attending continuing education classes, and knitting tiny clothes for my favorite small people. Commentariat, you good? After 20 years, I’m looking forward to my regulars perhaps choosing different hills to die on than the usual, if only for novelty’s sake. Surprise me! Some of these books certainly did.

Alana: As a newbie, all hills are unfamiliar territory for me, but let’s explore some new ones for your sake. I’m excited to get back into things—especially with this matchup!

Meave: Well, I’m glad to be back, and I’m very glad to have you as my partner in commentating. Shall we? I strongly disagree with their decision, but Schnelbach wrote a hell of a judgment, and I’m grateful both novels found an appreciative reader. I advocated hard for Boys Weekend to be included in this year’s Tournament, arguing in part that it’d be interesting to have multiple works with graphic elements. I didn’t expect these books to go head to head, though. Alana, how do you feel about comics or graphic novels, or works that include a lot of graphic elements?

Alana: It was a delight to read Judge Schnelbach on this pairing. I didn’t necessarily think of the erasure poems in Blackouts as visual elements, so I appreciate them teasing that out. I wouldn’t have thought to read Blackouts and Boys Weekend in conversation, and this decision makes me want to return to them as a pair.

Meave: A sharp and generous reading of both works by our judge, I love it.

Alana: I don’t read comics or graphic novels often. With the type of world Boys Weekend built, though, I was glad to have the visual accompaniment. To read about “a remote man-made island in lawless international waters” is one thing, but to see it in action? Delightful! Horrifying! Existential-crisis-inducing!

Meave: Totally great, packed with oh-no, of-course gags. I’m no Mrs. Comics, but Achewood, for example, was very important to younger me: I think “I’m the guy who sucks / plus I got depression” on a, like, weekly basis.

Judge Schnelbach raises excellent points about the difficulty of understanding your history when its records have literally been excised. But queer history is still there—or, at least for now. Like, there’s the digital Queer Zine Archive Project; the LGBT Community Center National History Archive and Visual AIDS; the IHLIA, “the largest gay and lesbian collection in Europe,” is working on restoring the library of one of Dr. Hirschfeld’s collaborators and “the Netherlands’ first gay activist,” J.A. Schorer.

It seems to me that queer archives and queer studies—in all sorts of disciplines—are pretty vibrant in 2024. But maybe I’m lucky to be old enough to be even slightly aware of queer history preservation efforts. You’re a queer person and a trained archivist—what’s your perspective?

Alana: I go back to Judge Schnelbach’s experience of the Good Library here. Queer history is always present, but how much is accessible to young people? As with the narrator of Blackouts, my vocabulary around sex and gender came much later. In the meantime, I clung to small things that did speak to me, as Juan clings to the “coded queerness of the works that have sustained him through his life.” I think this is a common experience in youth. I’m thinking of many examples, but particularly Lars Horn’s Voice of the Fish. One thing they write about is that, as a child, they kept a list of facts about fish because there were so many examples of sexual or gender diversity among them.

Meave: I have to say, being a confused teen in the late ’90s/early ’00s was terrible. I wish I’d had even the wherewithal to look for knowledge in unexpected places as a child.

Alana: Right! I remember Michelle Tea writing about finding friendship through graffiti tags.

Meave: Michelle Tea made me want to move to San Francisco so bad. Reading her books in college was—indescribable. Fireworks in my brain.

Alana: I do wonder how similar or different this experience is for younger people today, given ongoing attempts to ban books, and the connectivity of the internet. To your point, the formalization of queer history can only come to fruition if this knowledge is shared, which the internet makes easier in some ways. Some of the sweetness of Blackouts seems to be that the narrator and Juan are “walking through dark rooms” and finding their way together.

Meave: That is a conundrum. I wonder how many queer information sites are auto-blocked at school and public libraries that use E-Rate (a federal program for discounted internet access that requires the institution using it to filter the internet; these filters vary pretty wildly in what they deem “inappropriate”). Blackouts is very online—mixed media, multiple narratives happening at once—for a book that seems to demand being consumed in analog. I did share Judge Schnelbach’s “claustrophobic,” choking-on-dust feelings, but unlike them, I found it all a bit oppressive, however much the judgment helped me better understand the appeal of those elements.

Alana: Ha! I do see what you mean about finding Blackouts oppressive. The crumbling Palace, the dying Juan, the wandering Nene, the lost history, it’s all a bit gothic. (To be clear: I liked these elements!)

Meave: The “hunt your own clone” section of Boys Weekend really stuck in my head: Being forced to regard yourself from the outside-in seems cosmically horrific (speaking of “physician, heal thyself”). But choosing to love that person enough to free them? And by extension, free yourself from that regard? Overwhelming.

Have we sufficiently discussed Judge Schnelbach’s strongest arguments?

Alana: I found their critical arguments about Boys Weekend to be the strongest, particularly on the note about characterization. Even here, I get more of a sense of who Nene and Juan are than I do Sammie and their friends. Why is Sammie putting themself through this gross-sounding weekend with horrible people? It doesn’t sound like that’s explored enough on the page. The character that seems to have the most perspective is Erin, while our protagonist comes off as vaguely…Charlie Brown-esque?

Meave: I wouldn’t compare Sammie to Charlie Brown, but, like the judge, I wonder what Sammie’s and Adam’s friendship was like before Sammie came out. If Adam is so uncomfortable with this version of Sammie, why does he still ask them not only to be in the wedding party but to be the best “man?” Still. I liked spending time with Sammie more than with Nene and Juan—at least Sammie started from a place of joy, you know?

Alana: Yeah, I weirdly think the Wall of Bros would be richer if we got more of the Adam/Sammie relationship. I also see the argument for more horror. Like Judge Schnelbach, I have spent an unfortunate amount of time around Tech Bros, so I can understand why they would want more of the stuff that you (hopefully) do not get every day.

Meave: Oh, they’re inescapable.

Alana: I do also think Judge Schnelbach compellingly illustrates the sense of wonder one can feel sifting through all the layers of fact and fiction that commingle in Blackouts. I saw these layers forming a structure that undergirds queer history as we understand it today. Not just a thing we sit atop of, but a blueprint for how to know ourselves, build our stories, and understand each other. But I also see how these elements can distract rather than cohere.

Meave: I would read a collection of the erasure poems!

Alana: They were very moving on their own. There could be something disorienting about the way they’re used. The graphic-novel format has clearer guidelines for how image and text work together to form a story.

Meave: Boys Weekend does some great work within those constraints! I loved that the judge recommends people read both books. Like, if possible, developing one’s understanding of visual language is as important as the ability to discuss the written word. I hope other people feel similarly; I’d love to have more works that incorporate visual elements into their narratives in future ToBs.

Looks like next up we’ve got Chris Bachelder and Jennifer Habel’s Dayswork, featuring discourse on Herman Melville, Covid, and Herman Melville (also, Herman Melville), facing Tom Rob Smith’s Antarctic sci-fi thriller Cold People. Judge Anna E. Clark will preside with John and Kevin commentating.

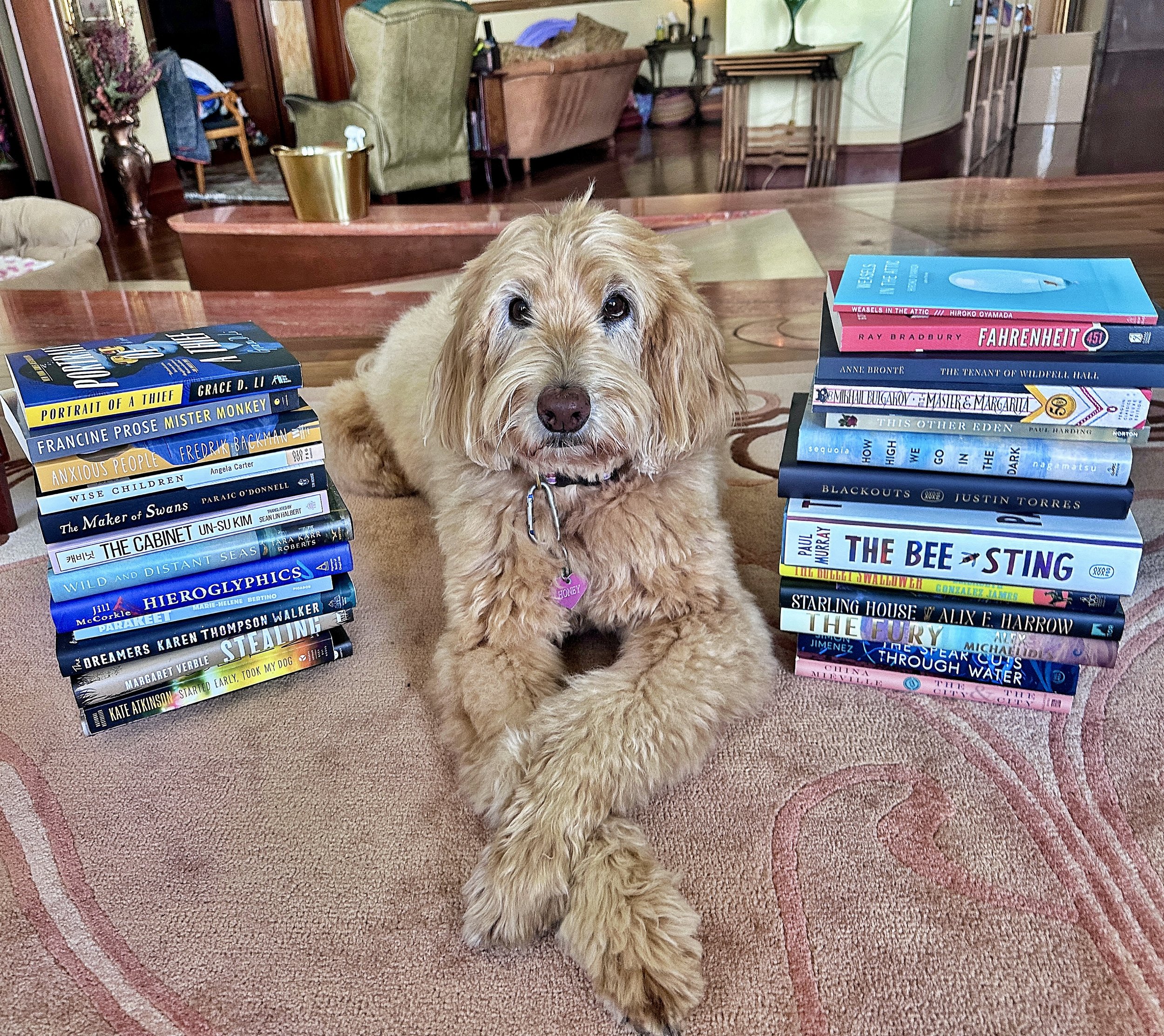

Today’s mascot

Welcome ToB mascot Honeysuckle, nominated by Evelyn, who says, “Honeysuckle is a multi-generational Australian Labradoodle. (Basically her breed is the ‘O.G. Doodle’ that started all the doodles.) She would make a truly excellent bookstore dog, but has to settle for overseeing her family’s private library. She is shown here taking a break from her cataloging duties. Honeysuckle’s preferred literary genre is anything that makes her mom SIT and STAY and read. Fortunately ToB never fails to increase the ‘to read’ stacks. Every. Single. Year. She wishes to express her profound gratitude to the Tournament.”