Blackouts v. Dayswork

The 2024 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among 16 of the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 19 • QUARTERFINALS

Blackouts

v. Dayswork

Judged by Nicole Acheampong

Nicole Acheampong’s (she/her) writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Aperture, The New York Review of Books, and elsewhere. She's an editor at T: The New York Times Style Magazine and is based in Brooklyn. Known connections to this year’s contenders: None.

Evasion can be pretty, and also very moving. I love a roving book that teases me, ducking and weaving. Both Blackouts and Dayswork start by dangling romance, then withdrawing. In Blackouts, there’s the fable-esque Palace in the book’s very first line, but the fable is quickly brought down to earth by chapped lips and wheezing sounds in the lines that follow. Dayswork opens up with “Bon voyage” and then goes domestic with frozen waffles and disinfectant. These books are in fact deeply interested in romance, but they are also coy.

Dayswork is clever and slender. Jennifer Habel is a poet, and many of the sentences have a lilt, and most of the paragraphs are spare. The narrator’s husband is causing her some sadness. It feels almost like an overstep to say that their marriage is troubled, because the narrator holds the exact details of that trouble very close to her chest, but I can definitely say that the husband looms and that he is also not as present as she would like. For her part, the narrator is both obsessive and avoidant. Her main obsession is Melville, whose life she lovingly dissects and inspects over the course of the book. Along the way, she avoids: saying the name of one prominent Melville biographer; saying too much about the aforementioned husband; and telling Melville’s story straight and linear, instead preferring to interrupt herself before she eventually circles back to herself.

Because the detours were so neat, I found myself, at several points, slipping into autopilot while reading.

Those tangents aren’t meandering ones. Instead, each one seems carefully measured, formal and academic like footnotes. And, much like traditional footnotes, many of those tangents offer new or somewhat surprising information, but few of them feel revelatory on an emotional level. Because the detours were so neat, I found myself, at several points, slipping into autopilot while reading.

There were, however, some key exceptions, passages where the book’s strict precision makes the narrative feel, maybe paradoxically, quite wrenching—namely the chapter that starts like this:

This morning I was once again denied access to “Some Psychological Reflections on the Death of Malcolm Melville” in the Winter 1976 issue of Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, so I stared out the window for a while.

So I reread the so-called “Malcolm Letter,” written by an exuberant Melville on the occasion of Malcolm’s birth—

…and then, just a little further down:

So I ordered more dog food and more coffee filters.

…and then:

So I threw the ball for the dog.

And then, later on, a list of facts, numbered one through 16, that measure out the day on which Malcolm, the oldest son of Melville and his wife Lizzie, committed suicide. The trick of that chapter is that it leads with Malcolm’s death, and yet, having been lulled by the narrator’s digressive style, I still didn’t see that ending coming—an effectively jolting way to tell a painful story. After the list of facts, the narrator’s husband briefly reappears, so that the two of them can inspect the story of Malcolm together. Then, at the end of the chapter, the narrator withdraws again, saying, “I knew Lizzie dressed the body but I kept that to myself.” The strange beauty of that line is that she is simultaneously keeping and confessing a secret, trusting us readers to hold onto something that she would not admit to another.

FROM OUR SPONSOR

When I sat down to write this judgment, I told myself not to write about the spider, because comparing stories to spider webs is definitely cheesy. But for a few days now, I’ve been lightly obsessed with this spider, and I feel pretty goaded by both Dayswork and Blackouts into giving in to my obsessions a little bit more. So: I’ve been watching YouTube videos of a Darwin’s bark spider—“no bigger than a thumbnail,” per the David Attenborough voiceover—that builds webs that stretch across the width of a river. The spider produces extremely tough silk, tougher than Kevlar, per multiple sources, but what interests me most is that when she’s spinning her web, the multiple strands look from afar like just one single thread, and they look like that because the spider methodically “crimps” (Attenborough’s word) them together as she spins them. And I think Dayswork is like that. Methodical and intricate and a story that looks, in certain lights, like it all coheres around one single thread.

The other thing about the Darwin’s bark spider is that if the threads are cut, she can pull them in and eat them later. I’ve been very stuck on that bit, the spider spinning and then eating and then spinning and then eating her own web, and that’s what I think about Blackouts.

That’s to some extent because the book is interspersed with a set of erasure poems, which take apart and then remake accounts from a study on early-20th-century queer subjects. And it’s to some extent because of the book’s endnotes and postface, where the story that we’ve just been vacuum-sucked into for nearly 300 pages gets sort of undone and then only partially remade; Blackouts playfully leaves some threads hanging. But it’s mostly because the characters are coming undone, too.

They’re stories about storytelling, so both of them incorporate a fair amount of meta literary criticism.

Blackouts’ narrator, like Dayswork’s, is unnamed. He’s a young, amnesiac man who’s traveled west, to visit with an old man named Juan, who is dying. They stay together at the Palace—a place that seems to be either a hospice or an abandoned building, or a shifting dreamscape—where they tell each other stories in the night, including the story of the research study, which is a real-life publication but which, in this novel, is also laced through with myth.

Unlike Dayswork’s narrator, with her careful evasions and equally careful divulgences, Blackouts’ narrator seems to be revealing himself in spite of himself, rendered vulnerable and malleable by the quiet, dark privacy of the room where he spends his nights talking to Juan. Many of the book’s chapters consist almost entirely of the characters’ dialogue, and the stories the two men tell each other transport them to other places, other time periods. Sometimes, they use the present tense to talk about things they’ve left behind or people who have long since become ghosts.

Yet these moments never feel indulgently enigmatic or cagey in the way that Dayswork can feel. When the characters of Blackouts were transported, they brought me with them, meaning I could look directly at their jumbled memories, rather than looking at the characters, from afar, as they remembered. That intimate style invited me to read with my full attention, and I read the book rapidly, with an urgent curiosity and the confidence that my curiosity would be rewarded.

Blackouts and Dayswork are experimental novels with an academic bent—they’re stories about storytelling, so both of them incorporate a fair amount of meta literary criticism. But Blackouts feels less like a carefully calibrated, intellectual exercise and more like an emotional stream of consciousness, the academic references as impressionistic and revealing as vignettes from the characters’ past lives. Juan frequently quotes other literary texts, and at first the citations are precise, but soon, as he becomes undone by sickness, they’re a mess. “I can’t quite recall who’s speaking, nor can I recall the passage in full, the proper order of the images…” he says at one point. “I think I may close my eyes now, drift off somewhere else for a bit.”

The drifting, the mess, and the shapelessness made this a book I could fall all the way into. Near the start, Juan asks the narrator for a story. “Please. Just one thing. Make it terrible,” he says. The phrase is repeated, make it terrible, and somehow it reads like a benediction: permission to unravel, to hold the ugly innards up to another, to say, Look.

Advancing:

Blackouts

Match Commentary

with Kevin Guilfoile and John Warner

Kevin Guilfoile: Years ago I worked as a copywriter and creative director at an advertising agency owned by Field Notes co-founder and proprietor Jim Coudal. At some point, as I recall, a client responded to one of our presentations by saying, “That’s good, if you like that sort of thing.” We found this hilarious as a tautology—an irrefutable, true statement that could be applied to anything—but also useful to describe a lack of interest in something that is, nevertheless, skillfully done. We said it all the time around the office.

For me, it’s a phrase that applies specifically to these two novels.

If not for the Rooster, I would not have picked up either Dayswork or Blackouts, and I just didn’t engage with either of these books in the way that I hope to when I’m reading fiction. It has to do with the experimental nature of each, the paucity of narrative, the unnamed characters. These are things that usually cause me to leave my keys at the front desk.

On the other hand, I have enjoyed reading thoughtful judgments (and comments) by people who do like this sort of thing. Judge Acheampong does a fantastic job of describing the things these novels do well. I liked reading about why she likes them more than I liked reading them myself.

In the last round I said that the parts of Dayswork I liked best were the parts detailing the ways various people, including the narrator, loved Melville, even though I do not.

Put another way, I don’t generally like cake, but I very much enjoy The Great British Baking Show. For some reason I like watching people make cake, even if I don’t want to eat the thing at the end. Likewise, I enjoyed reading along as Judge Acheampong (and others) deconstructed Blackouts, even if I didn’t especially enjoy reading it myself. I can see that it’s a good cake, though.

My appreciation of these books is so meta, John, that only a ridiculous Tournament of Books can access it for me.

John Warner: I really appreciated this specificity of the observations in the judgment because it asks us to look closely at the elements these books are made out of—because that’s where the juice for these particular novels comes from. They have character and plot and all that stuff, of course—they’re novels—but to appreciate them you have to be into the sort of thing they’re up to, and if you like that, you’re going to really like it because they are unlike most of the other novels out there.

While weird-ass novels often do well in the ToB, truly experimental novels tend not to make it to the champion’s spot. I would say that Interior Chinatown is probably the most experimental novel to ever take the top prize with its script within a novel and other formal experiments. Other than that, maybe Cloud Atlas—in the first year of the Tournament—with its structural games?

Kevin: Both of those novels are particular favorites of mine, btw.

John: In the case of this matchup, clearly an experimental novel was going to make it through since they’re both experimental novels. But we should note that Blackouts has already won the National Book Award (as did Interior Chinatown).

I think it’s hard for experimental novels to get traction with broad readerships, but every so often one seems to get a hold of lots of people.

Personally, I’d love to see publishers take more swings with more experimental novels given that they do have success with some frequency.

Kevin: Checking the Zombie results, we find that Dayswork does not have enough votes to stay alive in the tourney. If the Zombie Round were held today, Chain-Gang All-Stars and The Bee Sting would be our Brain-Crazy Bibliophiles.

Today’s mascots

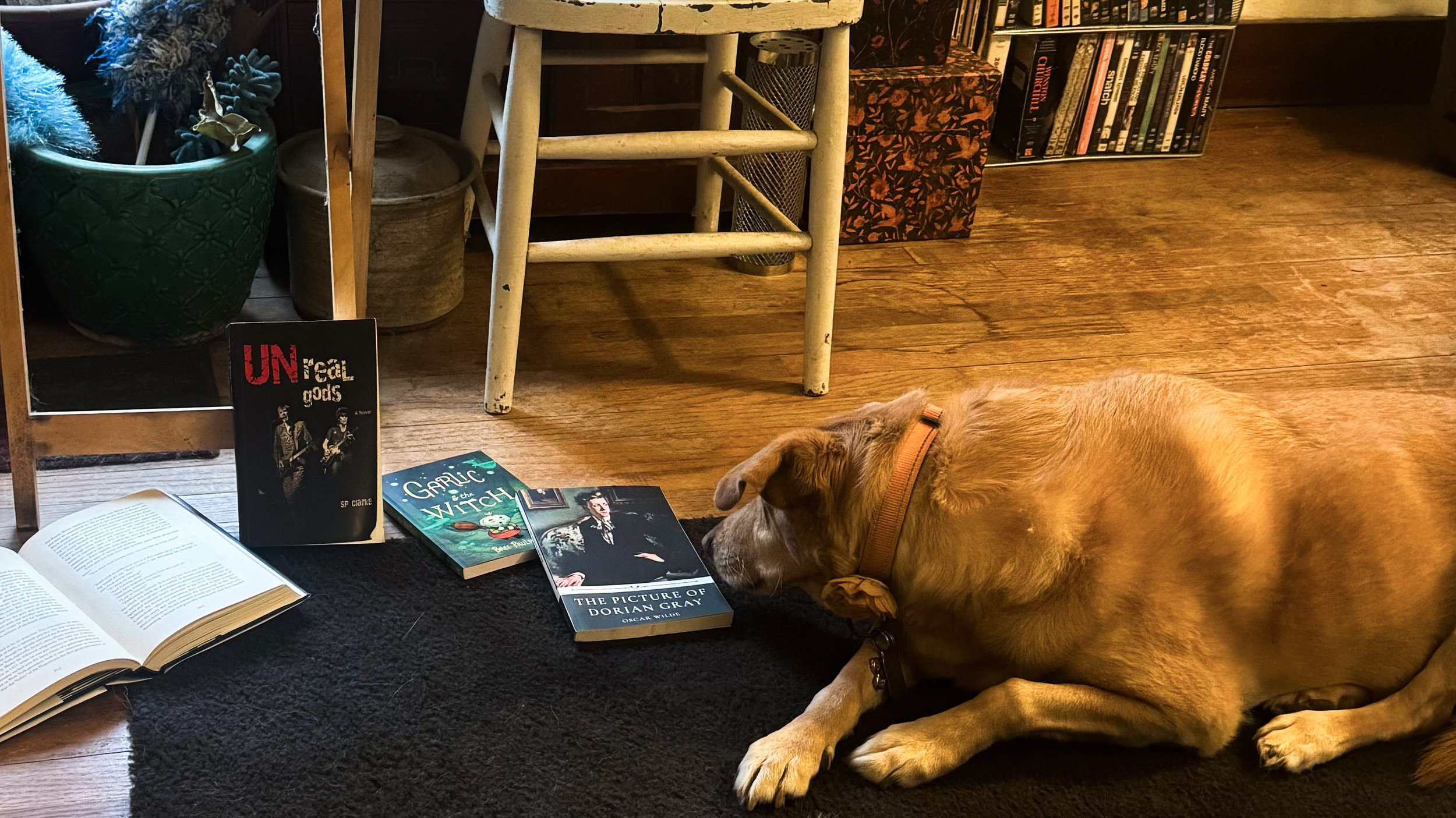

Nominated by Lesley, say hello to today’s mascots, Benjy and Beanie!

Benjy, aka Benjamin Benson McGee, is a Norfolk terrier mix who prefers sci-fi and adventure stories.

Beanie, aka Beanarina Velvet Ears, aka Blyssie Bean, is a golden lab mix who leans toward the classics and literary fiction, especially those by women authors.

Benjy is the alpha. Of the entire household. Beanie is a goofball, who will spook if you shift your foot.

Given that they have such different literary tastes, the Tournament brings with it a certain amount of sibling rivalry to this furry pair as they’re very invested. Beanie took a victory lap around the backyard last year, with The Book of Goose; Benjy felt pretty smug the year before when Klara and the Sun captured the Rooster.