The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store v. Open Throat

The 2024 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among 16 of the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 11 • OPENING ROUND

The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store

v. Open Throat

Judged by Dan Kois

Dan Kois (he/him) is a longtime writer and editor at Slate. He's the author of three nonfiction books, Facing Future, The World Only Spins Forward (with Isaac Butler), and How to Be a Family. His first novel, Vintage Contemporaries, was published in 2023; his second, Hampton Heights, will be published in the fall of 2024. He lives in Arlington, Va., with his family. Known connections to this year’s contenders: “I already read and did not vibe with Blackouts so I would not recommend giving me that one. I reviewed The Bee Sting for Slate (generally positively).” / dankois.com

OK, it’s a sunny morning in Los Angeles and you and a friend are going for a hike. You put on your gear and fill up your water bottle and lace up your boots and meet your friend at your regular lot in Griffith Park. And you head up the mountain along the bends of the pathway through the sage and manzanita, drinking lots of water because the sun is hot, and you and your friend talk—you really talk. You have one of those human conversations that winds like the trail itself, doubling back and making unexpected turns and leading you someplace real. You talk about your ex-boyfriend and she talks about her ex-husband. You talk about how the money’s running tight and she talks about the secrets she’s keeping. You talk about careers and fame and art and disaster. Your voices fill the trail, darting through the brush, echoing sometimes off the rock walls of the hills.

Who else is listening?

The hero of Open Throat is listening. The hero of Open Throat is a mountain lion, unnamed throughout the novel, who lives in a cave somewhere under the Hollywood sign, thirsting, hungering, remembering, and listening. It—a word, in a moment, on pronouns—spends its days holed up in the shade as humans tromp past, their endless chatter endlessly fascinating to this animal. As I read Open Throat, I thought about my own hiking trips, and how I must have looked and sounded to the animals whose habitats I was tromping through.

The humans in Open Throat are pure LA, ellay as the lion hears it. The novel presents snippets of their dialogue, uncut, but heard through a mountain lion’s ears, which comprehend, like, 95 percent of what they hear:

that’s the thing with ellay says the other hiker forget about therapy you have to go to the next level here

all we’ve got here is gurus

The lion dreams of being human, in a way that reflects both its limited understanding of humanity and its deeper insight into what we don’t see. It dreams of going somewhere “where there are therapists running around everywhere like deer and I can just find one and catch it and pin it down.”

I would not say the lion’s queerness is a crucial aspect of this story, though it does add a rich second flavor to the lion’s hunger for a certain well-muscled man it sees performing in the park.

(The jacket copy for Open Throat uses the pronoun “their” for the mountain lion, presumably at author Hoke’s request. At the risk of objectionably misgendering a fictional feline, I am sticking with it/its, because one point of the book is that no matter how much contact the lion has with humans, no matter how much it listens to us, it is still resolutely a wild animal—it is not a human, fascinatingly, terrifyingly so.)

(Speaking of issues of identity, the jacket copy also tells us the mountain lion is queer. It’s true that in its stories of the past, the lion does recall a deep love for another male mountain lion who shares food. I would not say the lion’s queerness is a crucial aspect of this story, though it does add a rich second flavor to the lion’s hunger for a certain well-muscled man it sees performing in the park. The jacket-copy mention feels a little calculated, meant to promise a subversive frisson that isn’t actually exactly in the spirit of the novel—though I should note the novel pokes at hidebound readers like me, playfully, with a human hiker, an industry type, noting that of course a project they’ve been offered is gay: Everything is gay now it’s all gay everything is gay now.)

FROM OUR SPONSOR

All of Open Throat is written in stream-of-consciousness monologue from the lion, short unpunctuated bursts of thought and impulse and misunderstanding. Once you get into its rhythm it’s totally enjoyable, even propulsive, offering some of the same snack-sized pleasures as reading a really good Twitter feed, only you don’t have to feel bad about it.

when I leave the cave the birds are screaming and there’s an even bigger sound in the sky

whirring and grinding and moving in long circles

the young man in town calls them fucking helicopters

the fucking helicopters circle at night and shine big lights down that take away my dark and then I can’t see and I can’t stay hidden

One thing I really appreciate about Open Throat, as I’m reading it, is its subtitle: a novel. I’m a big fan of books that shrug off expectations about what a novel must include, or how a novel must be shaped. Open Throat is 156 pages long and, due to its verse-like structure and very short paragraphs, can easily be read in a single sitting. It resolutely refuses to exit its main character’s extremely blinkered point of view, never strays from the mountain lion’s voice, and is only as interested in its humans to the extent that its hero is. Which is to say, sometimes its humans are interesting as people, and sometimes they are merely alluring as meat. I think that writers and publishers sometimes get too hung up on ideas of what a novel is supposed to be, and I really love a book that is clearly written exactly as it should be written—Open Throat should not be longer, and it should not include, like, a long omniscient disquisition on climate anxiety—simply claiming the mantle of a novel. Yeah it’s a fucking novel! Why not? Why can’t a novel be this?

The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store, on the other hand, is exactly what people have always thought a novel is—indeed, its resolve to deliver exactly what novels were built to deliver is one of the most enjoyable things about it. Novels should transport us to an unfamiliar time and place, this novel declares, and Heaven & Earth’s Pottsville, Pa., circa the Depression, is imagined right down to its tiniest bolt, from the shacks of Chicken Hill to its Jewish theater, to the white machers who wheedle and connive and influence behind the scenes. Novels should strive for capaciousness, this novel seems to believe: If a character is even mentioned in passing, Black, Jew, or goy, they’re likely to get their own chapter at some point that tells their whole dang life story. Novels should feature rich and suspenseful plots, this novel insists, and The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store keeps the pages flying. It opens with a mystery, a buried skeleton, and as we spend the whole novel learning whose skeleton it is, we also get twist after twist: a boy sent to a terrible institution; a kindly husband with a secret, violent past; a magical Hasidic dancer who returns from time to time to sprinkle whimsy on the story; illnesses and explosions and assaults galore.

Did I wish, at moments, that someone had given The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store a slightly closer edit, so that we didn’t read about Fatty’s 1928 Ford quite so many times on one page? Sure.

All of this is to say that unlike Open Throat, which presents us with an alien life and holds us carefully at bay, perhaps for our own protection, The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store means to immerse us in the welter of humanity—it has a touching faith, in fact, in the power of fiction to put us right into the shoes of people totally different from us. My pal Laura Miller has written at length about McBride’s devotion to representing entire communities in his novels, and how that vision of true multiculturalism reflects the greatest challenge facing Americans today: “figuring out how so many different people—espousing so many diverse and sometimes conflicting identities, histories, and beliefs—can become one people without denying those identities, histories, and beliefs.”

The characters in this novel, most of them at least, serve their purposes in fighting this battle, even if, at times, they are momentarily defeated by the noise and bustle of the country they live in. “The old ways will not survive here,” Moshe Ludlow, theater owner, writes to a friend in the old country. “There are too many different types of people. Too many different ways. Maybe I should be a cowboy.” And yet the novel’s good humor never fails, and its characters still do the things that need to be done, even though it requires struggle and pain. I laughed a lot reading The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store, ruefully admiring the book’s vision of America the way that every spring a crew of Black workmen look at the run-down historical house they must repaint and scrub in anticipation of the town’s Memorial Day celebration. “They stood back and gazed at the old house with their hands on their hips, shaking their heads like a mother who had just washed her son’s face 10 times only to realize that he was just plain ugly in the first place.”

Did I wish, at moments, that someone had given The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store a slightly closer edit, so that we didn’t read about Fatty’s 1928 Ford quite so many times on one page? Sure. Did I occasionally sigh when I turned to a new chapter and saw that, once again, we were in a whole new character’s point of view, and once again I was gonna learn allllllll about them? Yeah, man. But each and every time, The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store creates a whole new person from scratch, and they’re vivid and funny and identifiably human. And it turned out that, as much as I admired Open Throat’s formally inventive portrait of a solitary creature with “so much language in my brain / and nowhere to put it,” what I needed most as a reader this winter was to be lost in a crowd.

Advancing:

The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store

Match Commentary

with Kevin Guilfoile and John Warner

John Warner: I appreciated Dan Kois’s perspective on Open Throat, illuminating what he sees as its approach and virtues, because this is a book that missed me entirely. It’s not that I can’t see where the praise is coming from, or what aspects of the novel it’s rooted in, but I experienced none of them personally in the 90 or so minutes I spent reading the book, as though there was a pane of glass between me and the readers on the other side who find the book compelling.

Kevin Guilfoile: I don’t know that I would call a novel I read easily in one sitting “uncompelling.” I actually found the end of the book to be quite satisfying. I was never immersed in it, though. I always felt like it was an academic exercise. Write a novel in the voice of a mountain lion. OK. Is it an idea that is sustainable across the length of a novel, though?

John: Maybe I read it too fast, maybe my guard was up from the praise I’d seen, setting the bar higher than it could possibly meet. I felt like every subtextual commentary we’re meant to glean from the mountain lion’s perspective was so telegraphed that it no longer worked as subtext.

The passage Kois quotes is a good example of the phenomenon. Read that passage without the specific mention of “fucking helicopters” and you have an interesting foreign perspective on human machinery, but just to make sure we get it, the little joke is tossed in. I can’t imagine anyone actually laughing at the gag, but everyone will recognize it as a gag, and so we say the book is “funny.”

For me, everything is too on the nose, too transparent, and even the marketing angle about the narrating mountain lion seems like an attempt to manipulate me through some kind of identity signaling, rather than letting me notice through my own reading—huh, interesting, this mountain lion seems to have a real connection to males of the species—and then letting me puzzle through that.

Kevin: You accept the premise at first because that’s part of being a generous reader. The narrator is a puma, let’s gooooo! One of the ways the novel reminds us it’s a lion, as Judge Kois points out, is that it calls LA “ellay” and it calls Disney “diznee,” because everything it “knows” about humans, it learned from listening to them as they hiked past its hiding places. So ellay and diznee are just meaningless phonemes rattling around its head, but it can make that joke about “fucking helicopters?” It knows what it means to lick its paws “to a regal polish.” It understands what it means to take pictures with your phone. It knows anatomically what lungs are, and scientifically what electricity is. The idea that these are concepts it understands, or even has names for, is not consistent with the book’s desire for us to believe this is a lion, even a precocious one, who is naive to the mysteries of the human world.

As a reader you try not to think too hard about this stuff—let’s gooooo!—but for the gimmick to work, there needs to be some ironic distance between what the lion thinks it is seeing and hearing and what, as human readers, we know it is actually observing. But much of the time the lion is just thinking like a human, and a fairly clever one. The novel is trying to have it both ways—it presents us with a narrator who’s supposed to be something like an apex predator Chauncey Gardiner, but then it also uses that character as a vehicle for relatively sophisticated thoughts and ideas. At some point I stopped believing in the exercise.

Maybe that point was when the lion thinks, “I feel more like a person than ever because I’m starting to hate myself.” That’s a funny line. But the level of self-awareness it demonstrates also undermines all the stuff that comes before and after it.

Writing is hard.

John: I’m not saying it’s a bad book, but the idea that we’ve got some kind of masterpiece on our hands is a real stretch. But maybe that’s just me.

Kevin: You’re right. That is an unrealistically high bar.

John: I don’t know if this is a particularly good literary term, but to me, James McBride writes not novels so much as “tales." Yes, the tales take the form of novels, but the book’s driving impulse is to do exactly what Judge Kois says: to build a world in which the events of the novel happen, and this may mean over-constructing some things, but in the way McBride works, better to go over than under.

I significantly enjoyed The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store, but I tend to agree with the criticisms that it maybe wanders a bit too far before it gets back to the story we were prepared to follow— like everything could maybe just be five percent tighter—but it’s a bit of a quibble. That said, as highly as I’d recommend The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store, I’d rank both The Good Lord Bird and Deacon King Kong above it when it comes to McBride doing what he does, particularly The Good Lord Bird, which for me is like McBride channeling the best parts of Twain while infusing it with his own spin.

I consider McBride one of our best working contemporary novelists, so this end feels like justice for me.

Kevin: For some reason I was also a little less invested in this novel than in McBride’s previous books. I enjoyed it plenty; McBride is a treasure. But then when I finished I read the acknowledgments and learned that the novel was a tribute to the Jewish counselor of a camp for handicapped children in eastern Pennsylvania where McBride worked for several summers in the 1970s, and it imbued the entire novel with another sense of meaning for me. The themes of community, protection, empathy, sacrifice, and love were suddenly made personal to me in a way they hadn’t been when I was reading. It was a single piece of information that clicked everything else into place. Of course, a novel has to succeed independently of such intel—and clearly The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store does. But when I shut the book after those three pages of acknowledgements, I was really quite moved.

Tomorrow Debra Magpie Earling’s The Lost Journals of Sacajewea takes on Jen Beagin’s Big Swiss. We have the day off, John, but I know Big Swiss is one of your favorite novels of 2023.

John: Big Swiss was the first book I read in 2023 that I said had to be in the Tournament because to me it was just so weird and “specific,” if that makes sense, so I’m one reader who will be tuning in, rooting hard for a victory.

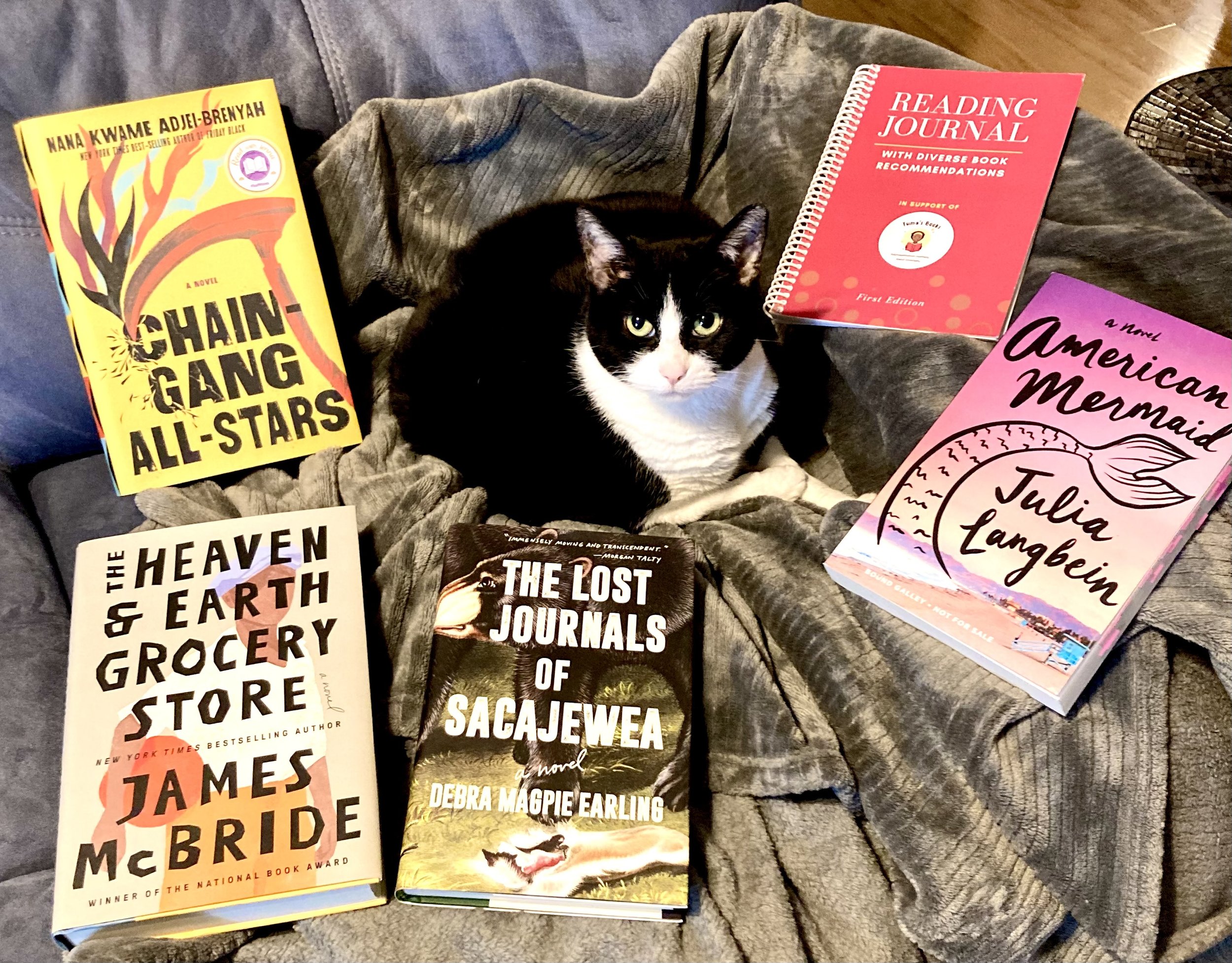

Today’s mascot

Today’s ToB mascot, nominated by Lauren, is Apollonia—aka Appy—a shorthair tuxedo cat living in Austin, Texas. She enjoys hiding in laundry baskets, collecting catnip mice, and tricking her parents into giving her extra food. Appy prefers the MySpace angles for photos, so she only approved one of these. She loves tracking her books in the Reading Journal, along with editing her mom's newsletter and Zooming in for the writing workshops. Thanks to her love of books, Appy has finished all shortlist competitors this year (minus two DNFs and the second half of Sacajewea, which she promises to finish soon). Her favorites this year were Open Throat (a cat's POV? Purrfect literary choice!), Chain-Gang All-Stars, and Blackouts.