Chain-Gang All-Stars v. Brainwyrms

The 2024 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among 16 of the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 14 • OPENING ROUND

Chain-Gang All-Stars

v. Brainwyrms

Judged by Stephen Krause

Stephen Krause (he/they) has been selling books for over a decade. Most recently he worked at Malvern Books and is currently a book buyer and cofounder of Alienated Majesty Books in Austin, Texas. He has also worked for Dalkey Archive, Deep Vellum, and The New York Review of Books. Known connections to this year’s contenders: None. / @franzlatke

The pairing of these two books was inspired. Both novels reflect humanist politics, and each of these titles is less than content with a realistic approach to them, choosing to engage through the lens of genre fiction. One hopes to teach an assumed common reader and the other intends to explore the edgelands of its own political geography. Both intend to satirize their material on some level, but only one fully commits.

In deciding how I needed to judge between these two books I realized I needed to be honest with myself about what moves me. I like a good story, but I don’t care for a prose style that functions largely as plot scaffolding. A lot of contemporary fiction reads like a pitch to film executives rather than discursive of film itself. Why do so many novels feel like they want to grow up to become a Netflix series? I want prose that reflects what only prose can accomplish, aside from being words on a page. I need to be shown fiction that is dedicated to the promise of its own imagination.

It’s not impossible to make good art with a clear moral and political aim, but it’s difficult to pull off satisfyingly.

I am wary of the didactic in art. It’s not impossible to make good art with a clear moral and political aim, but it’s difficult to pull off satisfyingly. Chain-Gang All-Stars stems from the subgenre of exploitation films about women in prison that has remained steadily popular since the early days of cinema. In dialogue with this lineage, the novel presents an almost-future world in which the incarcerated sign up to brutally murder one another with the promise of freedom after three years’ survival. They are stripped of all privacy so that the American public might watch (and rewatch) every desperate moment unfold.

It’s easy to read the book’s perspective on the voyeurism of sports fans and reality television intellectuals as commenting on the reader’s relationship with the narrative. Yet, does this commentary stick if the reader is granted knowledge of characters’ interior lives past what the book’s fictional spectators have access to? The floating cameras that follow their every waking moment—“Staxxx sat up in the water. An HMC watched her drip”—do not seem to implicate the reader as much as they do structural violence. So I often wondered why the action scenes are as engaging as they are. It makes sense if we’re playing in the realm of exploitation to feel a thrill alongside the book’s fictional spectators. It is only in these fights, the arresting chapters narrated by Hendrix Young—“What owns me is my own wrong and nothing else”—and in the footnotes where the language diverges from merely serving the movement of the story into something bolder. Most distilled in the margins, Chain-Gang All-Stars serves science fiction acronyms, US legal precedent, prison statistics, and obituaries that allow the murdered a final say. “I seen the best I’ve seen in the hole you keep the decrepit, so suck my dick.”

FROM OUR SPONSOR

Brainwyrms’ boldness makes itself known immediately, whether in the self-aware introduction—“My name is Alison Rumfitt and I am a cisgender woman. That’s what I’ve decided”—or on the first page of the story: “The sea, if it was the sea, was the consistency of spit.” Brainwyrms excoriates the society that would so traumatize its queer people they become the pharmakon for their own cultures’ self-inflicted illnesses. Brainwyrms is not a good story. It is the slippery carcass of a pulp paperback filled to bursting with fetid bacterial life, wretched with a necrotic hangover. A dull knife with a ragged edge. A wound gently fingered twice daily for a week, to be taken with food. It is also a polemical horror novel with a crooked smirk, ripe with an erotics so filthy it reminded me of the first time I read Story of the Eye.

Unlike Chain-Gang All-Stars, which seems to be more interested in making the argument for prison abolition to those who might struggle to envision a world without jailed rapists and murderers, Brainwyrms makes no arguments as to the validity of queer existence. Instead of spending the novel convincing readers that trans people exist, Brainwyrms would rather show how transphobia and other institutionalized delusions destroy trans lives and fracture queer relationships already fraught with the business of living. A chapter named “Arsehole” caps itself off with the sentence, “Through elastic time, they inverted one another,” commenting on what two lovers might do differently with their shit as their relationship splinters irreparably. The novel is messy, but earnest and uncompromising. My favorite chapter that I read in 2023 is in this book. It’s called “Piss Ghost,” and it starts, “I pissed in a haunted public bathroom the other day, the last public bathroom in Britain, and it was haunted. A girl crying beneath the urinals.”

Its story is good, and the point of it falls flat.

Hear me out. While reading these I thought a lot about something the director Francois Truffaut said in an interview with the Chicago Tribune in 1973: “I find that violence is very ambiguous in movies. For example, some films claim to be antiwar, but I don’t think I’ve really seen an antiwar film. Every film about war ends up being pro-war.” The sentiment here is that art which creates spectacle is going to have a tough time criticizing without glamorizing, sheerly due to the scale of a film screen, or the felicity with which language might describe a blade parting the skin of the throat. I felt as if Chain-Gang All-Stars was overly enthralled with its own theatrics, while attempting to problematize the impulse to be entertained by them. Its story is good, and the point of it falls flat. If Chain-Gang All-Stars incriminates the reader, it also compromises itself. I also wish its abolitionism was more radical and reaching. Science fiction should be looking further than the obvious, daring to be wrong.

Brainwyrms dares to be wrong throughout. Its horror is a head-splitting chop into imagined realms that center the doomed relationship at its core. Even when its experiments are ill-conceived performance art dialogue, it’s scraping beauty from a blister. After reading it, I immediately wanted to discuss whether or not the central relationship could function properly without the extra-dimensional horrors (transphobia) that are intent on consuming it. I wanted to talk about how culture directly influences fetishes, and whether or not a bad fetish can be partially blamed on the decrepit structures that continue to tighten themselves around the most vulnerable people among us. Where Brainwyrms succeeds is that it is not only in conversation with horror, but that it is fully immersed within it. Where Chain-Gang All-Stars is a humanist plea selling spectacle, Brainwyrms is a scream torn from an unwilling larynx. It is a diagnosis reveling in astonishment.

Advancing:

Brainwyrms

Match Commentary

with Kevin Guilfoile and John Warner

John Warner: When the books to be included in the opening long list for the Tournament were discussed, I read the description of Brainwyrms and said to myself: Nope, that one is not for me. Body horror and visceral gross-out material are not my things, and while I have no objection about books like Brainwyrms being in the world, it just isn’t something I’m going to read. This is purely personal, not an absolute judgment on the book.

Kevin Guilfoile: I turned 55 last year, John, which might make me the oldest, straight, cis man who has ever read Brainwyrms. Everyone should keep that in mind.

The novel does certain things well; I think the book succeeds in many ways as a political act. Like you, body horror is not a genre I enjoy in the least, but I recognize its utility as a metaphor for being transgender in a world where transphobia is routinely normalized. Intellectually, I understand what works here. Sympathetically, I am on Rumfitt’s side.

Judge Krause hints at it, but I’m not sure it’s clear how extremely graphic Brainwyrms is. Many will find it simply impossible to read. Incest. Gruesome scat play. Urophilia. BDSM. Necrophilia. Filicide. Gang rape. Self-mutilation. Parasitic worms that squeeze out of the eyes and genitals. A furry who eats their own shit. Imagine a book that actually has everything that Ron DeSantis thinks Toni Morrison put in Beloved.

Unsurprisingly, given all that, it’s also not subtle. The Big Bad in the story is a famous, female, British YA novelist who has written a blockbuster series of books about the adventures of a school-age witch and her friends. It’s probably difficult to overstate how many queer people of a certain age (and their allies) felt betrayed when JK Rowling voiced support for odious, anti-trans, TERF ideas, and clearly Rumfitt relishes making an avatar of Rowling into her own book’s Voldemort. If Rowling is ever curious enough to pick up a copy and read it to the end, the message will definitely be delivered.

As a whole, the novel is deliberately and aggressively unpleasant, but where it really trips on its own, quite literal shit-covered entrails is in the treatment of its protagonists, lovers Frankie and Vanya. They are casually cruel in a way that makes it difficult to root for them in a horror narrative where that should be very easy, and especially when that sadism is played for smirks and laffs. Frankie and Vanya are engaged in a dom/sub relationship, and some of their behavior is understandable in that context, but plenty of it crosses the line:

On page 11: “Their knuckles were white. They could have punched the bitch and left her for dead. They probably should have.”

On page 94: Frankie and Vanya are having sex and Vanya concusses themself when they hit their head against the wall. Frankie continues to have sex with them even though they are clearly injured and incapacitated, and she compares it in her mind to necrophilia.

Frankie also deliberately misgenders Vanya during sex, which, obviously, is a seriously dick move. Vanya at least calls her out on it (and the incident has some significance to the plot), but Frankie is mostly unrepentant. Regardless, the problem here is that these are the good guys. Just from a standpoint of basic storytelling, Rumfitt runs a backhoe over every on-ramp the reader might take to feel sympathy for these characters.

She does an excellent job of being cruel to her darlings, but she does the reader a disservice when she makes her darlings be cruel.

Authors and readers are in a relationship, and the author needs to be a good partner. Of course it’s possible for a novel to have an unlikable protagonist, but it’s a tricky business, and Brainwyrms isn’t anywhere close to nuanced enough to pull it off. Imagine, for instance, what a different film Halloween would be if we saw Laurie being super-mean to the kids she babysat.

I have a trans nephew, whom I love very much. Trans rights are very important to me. And as a cis person who loves a trans person, I think it’s also important to try as best I can to understand the anger and dreams and hopes and fears of my nephew, but also other trans folk.

As I said at the top, there is some kind of audience for this that does not include me. There are three Human Centipede movies, after all. Nevertheless, I might be glad to have read Brainwyrms, even if, while I was reading it, I wished I was doing almost anything else.

John: Your response pretty much confirms my resolve to not read the book.

I almost also purposefully didn’t read Chain-Gang All-Stars, though for a very different reason. As long time ToB aficionados know I do a bit of schtick as “The Biblioracle” (at both a column for the Chicago Tribune, and at my newsletter), where I ask people to tell me the last five books they read and then I tell them what to read next.

(Real aficionados may recall that The Biblioracle was born in a ToB comment section, Kevin, when you and I were the only ones doing the commentary and we’d run out of things to say.)

As part of that service, I try my best to recommend a book where there’s some chance that it may not otherwise be on the requester’s radar. This means avoiding books chosen by Reese, Oprah, Jenna, etc., because those books are guaranteed a significant chunk of attention. I was a fan of Adjei-Brenyah’s previous book Friday Black, but when Chain-Gang All-Stars got the nod from Jenna Bush and the Today Show, I moved it to the way-back burner. If it hadn’t been one of our opening-round matchups, I probably wouldn’t have gotten to it, which would’ve been a mistake.

Kevin: Chain-Gang All-Stars is an unofficial satirical companion to the acclaimed Ava Duvernay documentary, 13th, which details the ways the US prison system takes advantage of a loophole written into the 13th Amendment that abolished slavery “except as a punishment for crime.” For 250 years this country has created a demand for cheap prison labor (many parts of the US still have for-profit prisons) that has led to the incarceration of African-Americans (and the revocation of virtually all their rights) in extraordinary numbers—the prison system having replaced, in effect, the plantation one. In the novel, the prisoners who sign up for this ongoing, reality-TV snuff show are exploited for millions of dollars in profit as the games draw Super Bowl-type ratings. It is a feature-not-a-bug of the competition that nearly all the prisoners die before they are able to claim their promised reward.

It’s a brilliant satirical premise. Adjei-Brenyah is a terrific writer, and his characters are beautifully drawn. Brainwyrms’ Frankie and Vanya seem like outlines next to Chain-Gang’s larger-than-life lovers, Loretta Thurwar and Hurricane Staxxx. The heartbreak at the climax of Adjei-Brenyah’s novel is truly and sincerely felt by the reader. It’s a far more powerful emotion than squick.

Judge Krause seems to think that, as a compelling story one could easily imagine as a Netflix series, Chain-Gang is too enjoyable a read when contrasted with its serious subject matter. I’ll parry that Truffaut quote with one by another celebrated director, 13th’s Duvernay, who, in a New York Times interview (gift link), noted that her documentary “about the prison-industrial complex,” released on, yes, Netflix, had been watched by many more people than another much-hyped studio film in theatrical release. “If I'm telling these stories to reach a mass audience,” she said, “then really, nothing else matters.”

John: I’m baffled by the reasoning and dismayed by the loss by Chain-Gang All-Stars. For me, the book works on a thematic, dramatic, and character level while also managing to be a page-turning thriller through the last third. I don’t know why we’d hold that against a book given how hard it is to marry all of those components. This is one of the more disappointing judgments to me personally in my long association with the Tournament.

Kevin: The preliminary Zombie results will start to roll out at the end of this round, so you and I will wait anxiously to see if Jenna, et al, were able to rally the votes that Chain-Gang will need for a return battle. In the meantime, how would you classify something as self-referential as tomorrow’s match, in which Patrick deWitt’s The Librarianist meets Michiko Aoyama’s What You Are Looking for Is in the Library? I think I’d file it under library science’s most meta number—025.431—which is where the Dewey Decimal System shelves books about the Dewey Decimal System. Dive into that rabbit hole at your peril.

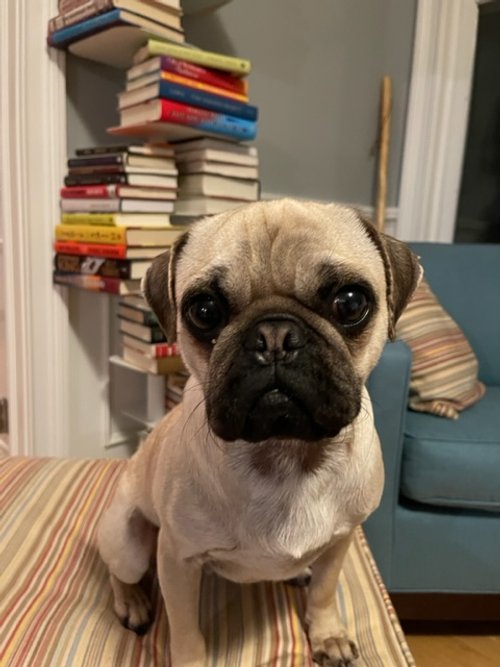

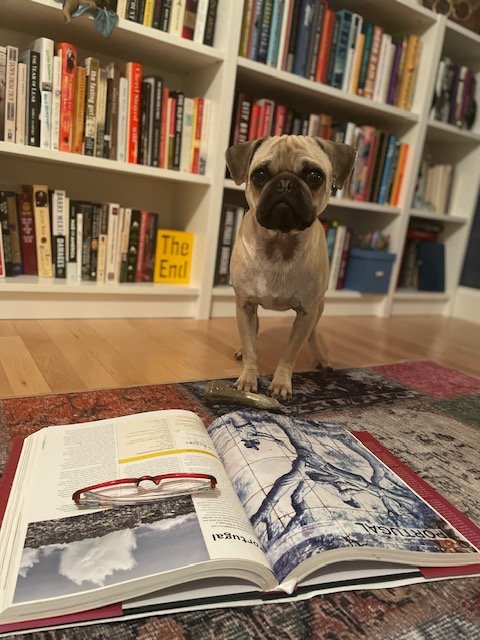

Today’s mascot

Welcome today’s mascot, Dash, nominated by JoDee, who tells us:

Dash is a pug who joined our family in November from Tiny Paws Pug Rescue. His favorite activity is wrestling with his sisters (2023 mascots Maizey and Shiloh), so obviously his favorite ToB book is Stephen Florida.

When he is ready to relax he loves to read in a big pile on the couch with the rest of his grumble. From this year’s books he most relates to Open Throat because of his (brief) period of abandonment in California, though his story ends with being spoiled on the East Coast.