The Rabbit Hutch v. Nightcrawling

The 2023 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 24 • QUARTERFINALS

The Rabbit Hutch

v. Nightcrawling

Judged by Katy Waldman

Katy Waldman (she/her) is a staff writer at the New Yorker, for which she writes about books, culture, and more. Previously, she was a staff writer at Slate and the host of Slate’s Audio Book Club podcast. She won the National Book Critics Circle’s Nona Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing in 2019 and the American Society of Magazine Editors’ award for journalists under 30 in 2018. Known connections to this year’s contenders: “I reviewed Dinosaurs and profiled Emily St. John Mandel.” / @xwaldie

If I were to graph my absorption in The Rabbit Hutch over time, it might look something like this:

Before I explain my very scientific graph, I want to commend the book because I kept thinking the graph was about to nosedive, and it never did. The main character, Blandine Watkins, is an ethereally beautiful, precocious genius who, at 18, is obsessed with female mystics, climate justice, and fighting evil developers in her hometown of Vacce Vale, Ind., a fictional place that, in the novel, tops Newsweek’s list of “dying American cities.” That’s a setup that feels dangerously close to twee. Also, the language had a mannered or stylized quality—“a dull financial angst pounds around her kidneys”; I worried its shine would wear off. For me, present-tense narration can make a book feel oddly trapped. But Gunty’s caught-in-headlights surrealism ended up serving the story. Her characters, too, are deformed painfully by their circumstances, institutions, and country. The novel’s distortedness ended up suggesting a sort of holiness, like an el Greco painting.

The book opens with Blandine exiting her body on the floor of her apartment. “She has spent most of her life wishing for this to happen.” She lives with three boys who, like her, have just aged out of the foster system, and Gunty implies rape or murder. The novel then skips backward to introduce other tenants in their crumbling building—the “rabbit hutch” of the title, where the walls “are so thin you can hear everyone’s lives progress like radio plays.” These characters are funny and sad and alive. Joan moderates comments for an obituary website; Hope, a new mother, has developed a phobia of her baby’s eyes. An aging starlet meets Death at a pet shop, where the fish remind her of America: “busy and doomed and theistic.” (Good stuff.) In one of the longest sections, Gunty conjures Blandine’s backstory, how a predatory teacher destroyed her academic promise. The guilt-ridden “nice guy” who yearns to be mothered by a highschooler is a familiar character, but Mr. Yager is perceptively drawn and troublingly sympathetic. And Blandine, wading through a complex snarl of loneliness and lust, proves that she’s more than a manic pixie dream girl.

Bonus points

+1 The witty observations about trying to be polite in a laundromat, the fact that a coffee shop’s selection of “avant garde pies” includes “charcoal banana” and “broccoli peach”

+2 The formal experimentation, including a chapter told entirely in black-marker drawings

+3 The sense, in a book whose characters constantly wonder whether they’re awake or dreaming, of violence and self-violence as the last recourse of people who feel unreal

Nightcrawling, by Leila Mottley, has an intensely single focus. Told in first person, present tense, it follows one protagonist, Kiara, who is hunting for work to support herself, her brother Marcus, and an abandoned nine-year-old named Trevor. Kiara walks the streets of East Oakland, where she is preyed upon by police officers; the novel is based on a 2015 news story about a ring of cops who exploited at-risk teenagers for sex. Mottley’s prose has an urgent, intimate, I-am-speaking-into-your-ear quality. My graph for Nightcrawling looks like this:

This is a book that pulls you deeper and deeper into one character’s brain and body. The better you know Kiara, the more you get a sense of her life, the richer the story feels—it’s a cumulative experience. (The Rabbit Hutch, by contrast, is spinning multiple plates in the air from the jump.) Nightcrawling is about growing up too soon and who gets to be a child. It’s also about children themselves: their weird logic, solemn infatuations, and kooky etiquette. Yanked into an adulthood of impossible choices, Kiara is trying to preserve the kid-like parts of Trevor, such as his enthusiasm for basketball and dance parties. Meanwhile, the grown-ups in her life, including her mom and brother, continually fail her. (Marcus, who dreams of making it in the music industry, refuses to get a paying job. Kiara’s mother lives in a halfway house and can’t come to terms with her responsibility for the death of Kiara’s baby sister.) There’s a lot of bleakness here, but Mottley’s empathy—the book loves its characters, you can feel it pulling for them—helps counteract it. The least transient parts of Kiara’s life are her relationships, and the fortification she draws from friends and chosen family is genuinely moving. The writing itself reflects Mottley’s tenure as the 2018 Oakland Youth Poet Laureate: supple and intelligent, vulnerability threaded with steel. “Ain’t this everything they said it would be,” Kiara thinks as a cop assaults her, “and ain’t I so sad to be familiar. Ain’t this just another night. So many ways to walk a street and I am still just a girl with skin.”

FROM OUR SPONSOR

I had a few quibbles. Several fist-pumping moments in which Kiara confronts various relatives felt unrealistic/hokey. A hastily sketched romance that seems to patch her world together in the last act isn’t quite earned. Mostly, the book made me think about the uses and pitfalls of creating an easy-to-interpret narrative that describes a hard-to-solve problem. As Mottley writes in her author’s note, Nightcrawling is written against a racist conception of Black womanhood and toward a truer or more representative vision. Truth value is just that—valuable—but I found myself looking for what made the novel specific or inventive or surprising enough to transcend Mottley’s stated political objective. For me, that answer lay in Kiara’s voice, which marries fierce open-heartedness to old-soul irony.

Bonus points

+1 The image of a swimming pool filled with dog shit; the image of a single, giant birthday pancake

+2 The eroticism of Kiara watching a girl skateboard, trying to “make my gaze so concrete and powerful that Ale would know I saw her more than her girlfriend ever could”

+3 The fact that Leila Mottley wrote Nightcrawling when she was 19

Wasn’t there some philosopher who defined beauty as the most complexity contained in the simplest possible expression? (I tried to Google it and found Hume—“each mind perceives a different beauty”—which is not helpful for a would-be judge. My mind perceives the one correct beauty!) But a lot of this decision did, in the end, come down to complexity. I guess I never grew out of loving the shiny thing, the thing that whistles and beeps and plays music while it tries to brush your teeth. Which is to say: If two books pack a comparable emotional wallop, I reliably go for the one that’s more intricate, experimental, unusual.

Here’s a more specific (retrospective) breakdown of my criteria:

Was I moved?

I honestly think I was moved basically equally by The Rabbit Hutch and Nightcrawling.

Did I cry?

Neither of these books made me cry. A number of book/movie/music reviewers like to describe how they cried while consuming a book/movie/piece of music. To them I say: Congratulations on your sensitivity! [in robotic monotone] I did not cry.

Structural complexity?

The Rabbit Hutch has the clear edge here. Nightcrawling plots one arc. The Rabbit Hutch plots at least five arcs and then twines them together.

Linguistic complexity?

On a sentence level, the advantage goes to Nightcrawling. Mottley sticks close to Kiara’s thoughts, so when something dramatic happens, the prose speeds up and starts to unravel. There are ambitious/involved metaphors, a few of which pull you out of the action because they’re hard to track. (Meeting this criterion can backfire.) Line by line, Gunty’s voice is sparser.

Moral complexity?

Look, I love a light/dark binary in literature. The marsh versus the mead hall, Goodman Brown versus the Devil, elves versus orcs! But if you’re not writing allegory or epic, I’m going to need some nuance. The Rabbit Hutch follows characters whose mixed motivations and strange behavior make them both mysterious and dynamic. There’s compassion, curiosity, and a commitment to observation rather than judgment. Kiara’s life, by contrast, has descriptive texture but not moral texture—we get pungent details about her experience, but she is always a woman in a difficult situation, trying to do the right thing. The cops who exploit her are muscles, badges, a gun held to her face. (Compare the slimy teacher from The Rabbit Hutch, who is always legible as a person—even an occasionally well-intentioned person!—albeit one whose self-delusions paper over the gap between those intermittent kind impulses and his grotesque behavior.) Nightcrawling isn’t supposed to be morally complex, you might protest, and you are correct. That’s exactly the problem.

Advancing:

The Rabbit Hutch

Match Commentary

with Kevin Guilfoile and John Warner

Rosecrans Baldwin: Before John and Kevin get going, I want to remind everyone to join us tonight for a free Zoom chat about all things Tournament of Books, brought to you by our lovely media partner, Books Are Magic. Reserve your spot here, and we’ll see you at 7 p.m. Eastern—me, Meave, Alana, judges Calvin Kasulke and Christina Orlando, plus a special guest!

And now here’s John and Kevin.

Kevin Guilfoile: John, I think this is the first Rooster judgment ever with graphs. Gotta love it. In the opening round, you and I talked about the fact that Nightcrawling has “a long on-ramp” and I think Judge Waldman has illustrated that with the hockey stick in her “absorption graph” of the novel.

John Warner: I’m thinking now that I abandoned Nightcrawling right at the moment Judge Waldman’s graph takes a little dip. I’m sort of kicking myself, except it happens, particularly in the ToB reading time of the year when I’m feeling pressure to at least have a taste of as many books in the tourney as possible.

Kevin: One thing I think I disagree with is Judge Waldman’s assertion that Nightcrawling is better written on a sentence level. Gunty has clearly spent years thinking about writing and has developed impressive chops. I think her writing is stunning and it shows in virtually every paragraph. Nothing in The Rabbit Hutch feels unplanned (which might be something Judge Waldman is reacting to). Kiara’s voice is arresting, but Mottley’s prose seems more instinctive to me. I don’t want to dismiss that ability in the least—good writing instinct is probably the most valuable attribute a novelist can have—but Gunty’s skills are undeniable.

On the other hand, I didn’t know until I read this judgment that Mottley was only 19 when she wrote this novel. Ho-ly shit, John. Are you kidding me? That’s incredible! Nightcrawling is a mature novel with a thrilling and authentic point of view. When I was 19, I was super proud to be writing movie reviews with dirty words in them.

John: I’m with you on the relative virtues of the prose in these books. I did not know that Mottley was so young either, which is pretty astounding as I consider my first forays into writing fiction at about that age and the deep shame I can still conjure thinking about what those stories looked like.

As I remarked in the previous round, I didn’t quite buy the connection between the character of Kiara and the fierce poetry and insights of the prose. I had this impression of that authorial intelligence looming over the character. I think I’m an outlier in terms of being bugged by these things, but I could muster an argument that it’s there.

Maybe this analogy works: It’s like a soloist who plays a lot of notes, showing off a virtuosity that is truly stunning (19!), but maybe isn’t always matching that virtuosity to the moment. The Rabbit Hutch’s prose seemed more—maybe “controlled” is the word? There’s a consideration working underneath the word choice that is just different from Nightcrawling’s improvisation.

Of course, that all could be wrong. The text itself could create an illusion in terms of what went into its creation. Gunty could have fired out The Rabbit Hutch in a furious fever dream, not changing a word after it hit the page. Describing the reader’s experience of the text doesn’t necessarily uncover the method of creation.

Kevin: No doubt. We all make a lot of assumptions when we read, and most of them are probably way off. I once did a radio interview to promote my first novel, and the intelligent and thoughtful host described how a character in my book was an allusion to the biblical Martha of Bethany. Her analysis was nuanced and brilliant. It made perfect sense and her explanation went on for several minutes. It was also the first I was hearing of it. In reality I had named that character on the day Martha Stewart went to prison.

Looking in on the Zombie results, Nightcrawling is not quite stealthy enough to make it into our top two. If the Zombie Round were held today, Babel and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow would be our mummified manuscripts. The semifinals start Monday with The Book of Goose and Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance.

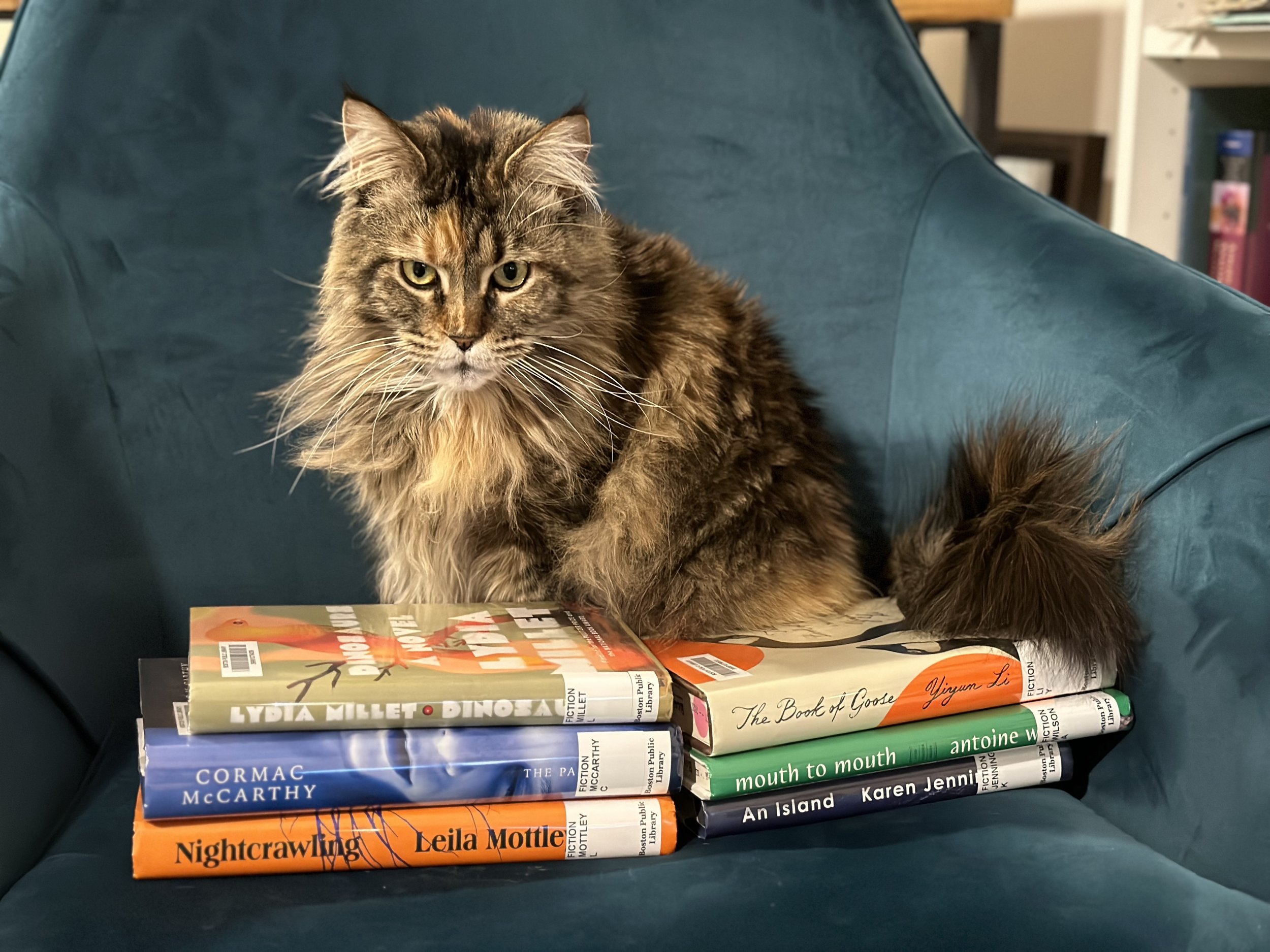

Today’s mascot

Today’s mascot, nominated by Maggie S., is Freyja! Freyja is a Maine Coon, a large and especially fluffy breed of cat. She is named after the Norse Goddess and strives to always maintain the bearing that demands. She loves laps, string, sliced turkey, and attempting to murder the birds that visit her window bird feeder. Curse that glass! She is an enthusiastic bibliophile and makes books her own every time she encounters them, although more by rubbing her cheeks on them than traditional “reading.” Her favorites are the heavy tomes that keep her human furniture in lap-mode for extended periods of time, so the ToB is one of her favorite times of year. She is very excited to meet you all and accept your tribute. Hail, Freyja!

Welcome to the Commentariat

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus <spoiler> tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “<spoiler>Dumbledore dies.<spoiler>”

We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.