The Book of Goose v. Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance

The 2023 Tournament of Books, presented by Field Notes, is an annual battle royale among the best novels of the previous year.

MARCH 27 • SEMIFINALS

The Book of Goose

v. Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance

Judged by Santiago Jose Sanchez

Santiago Jose Sanchez (they/them) is the debut author of the novel Hombrecito, forthcoming from Riverhead. They’re a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where they were a Truman Capote Fellow, and a current Mellon Fellow in Fiction at Grinnell College. Their stories have been published in McSweeney’s, ZYZZYVA, Subtropics, Joyland, and distinguished in the Best American Short Stories. Known connections to this year’s contenders: “Xochitl is a dear friend.” / @sntsnchz

I started The Book of Goose already a fan of Yiyun Li. I’ve been teaching her story “Extra” for several years now. Its protagonist, Granny Lin, doesn’t have a whole lot of agency over her life—she’s fired from her job, married to a widower, then sent to work as a maid at a boarding school—but even as her possibilities narrow, she manages to live with curiosity and compassion for the people around her. These are the kinds of characters I could read about all day, perhaps because they remind me of my mother—a woman who migrated to Miami in the late ’90s alone with two children, who had every reason and excuse to shut her heart off from the world, but didn’t.

The Book of Goose opens with Agnès just after learning that her childhood best friend, Fabienne, has died. They were inseparable as young teenage girls in rural France, but for years, Agnès has put as much distance as possible between herself and Fabienne, even moving to Pennsylvania, where she’s a mystery to everyone. This news of Fabienne’s death finally gives Agnès the freedom, the courage, and that more elusive thing—permission—to finally write down the story of their intense friendship. “Fabienne had explained to me, we will leave little opportunity for the world to catch us. Catch us how? I had asked [...] Just follow me, she had said, you do nothing but what I tell you to.” The larger world inevitably catches up with the wandering pair when Fabienne decides that they will write a book together to show the world how they lived. The book gets published with only Agnès’s name on the cover—Fabienne’s idea—and before Agnès knows it, she’s thrust into the world as a teen prodigy. Present-day Agnès narrates the series of events that took her to the publishing world of Paris and a finishing school in London, while Fabienne remained at home in their rural village, tending to farm animals. “I could be myself only when I was with Fabienne. Can a wall describe its own dimensions and texture, can a wall even sense its own existence, if not for the ball that constantly bounces off it?”

I recognized myself in Agnès. My own Fabienne and I hurt each other in every possible way without ever discovering who was the ball and who was the wall. Even after I left Miami for Yale, for New York City, for worlds far removed from anything we had ever imagined, I still thought of a future where my Fabienne and I would end up together, as best friends or lovers or some third thing. The thought that I was only a spy, learning how the rest of the world worked, so I could come back to him and tell him everything, sustained me those first years of our separation. I felt 19 again reading Goose. Like I was studying for a chemistry test, I took a picture of almost every other page. Agnès had found the answers for the cosmic and bone-deep questions that come with realizing you’re not half of a whole.

It’s here where the novel finds its footing as a coming-of-age tale in which I saw glimmers of a similar project as Goose: How to honor the past and break from it.

I was unfamiliar with Alison Espach’s work. I’d forgotten what it was like to start a book with zero expectations or prior knowledge. I didn’t even read the cover copy or blurbs. From the title and cover alone, I imagined I was going to step into a propulsive literary thriller like Celeste Ng’s Everything I Never Told You.

Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance does, in fact, open like a thriller: “You disappeared on a school night. Nobody was more surprised by this than me. If I believed in anything when I was thirteen, I believed in the promise of school nights.” The narrator here is Sally Holt, a young girl addressing her older sister, Kathy, who was killed in a car crash. The first movement of the book reveals how Kathy died. It wasn’t just any car crash: Sally was in the car, she had forced Kathy and Kathy’s boyfriend Billy to take her to school that morning. If it weren’t for her, Billy wouldn’t have been speeding to make it to class on time. This is the guilt Sally carries into the second movement of the book, during which she tries and mostly fails to come to terms with Kathy's loss during her own adolescence. It’s here where the novel finds its footing as a coming-of-age tale in which I saw glimmers of a similar project as Goose: How to honor the past and break from it.

Espach’s characters are easily recognizable archetypes of a suburban American adolescence, which is to say, they’re not really my people. Sally Holt is the younger sister forever in awe of the older sister who holds all the world’s answers. Kathy is a typical older sister; she has eyes and ears only for Billy. Billy is the high school athlete known for “putting a carrot in a pencil sharpener before lunch and jumping off the roof after school,” and yet there’s something about him that holds Sally and Kathy “like two beads strung on the chain of [his] life.” These three are caught in what feels like a love triangle, the emotional knot that Espach twists and tightens, and sees the story through to its romantic end. While Sally’s voice was surprising, and at its best bawdy, I couldn’t help but feel I would maybe never be in the same room as these characters. I wasn’t this book’s audience just as I wasn’t the audience for the dramas about suburban American teenagers that were on television when my mother brought me and my brother to Miami.

FROM OUR SPONSOR

I kept thinking of The Book of Goose as I read Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance. Agnès tells her story from a vantage point later in her life. Her attention is clearer, her voice sharp with age. The project of her story isn’t to make the reader experience childhood and adolescence again, but to dramatize the process of trying to make sense of the past. This is a project of revelation and illumination, of looking back and seeing every detail you missed. “We were not liars, but we made our own truths, extravagant as we needed them to be, fantastic as our moods required.” I trust Agnès’s vision. I want to learn from her.

On the other hand, Espach is more concerned with the experience of Sally’s coming of age. Her magic trick is to make the reader feel like they’re stepping back into adolescence, with all its desperate energy and cringe-worthy mishaps. Sally grows up as the story unfolds, in each chapter she’s older, the voice a little more grown, and her sense of the hole that Kathy left behind changes along with her, so that the addresses to Kathy take on a sadder, more desperate resonance the longer the older sister is gone. Everything else might change, but Sally is still talking to Kathy in her mind.

By the end of Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance, Sally is still trapped in a story that isn’t hers. Sally is a 28-year-old in a stable but bland relationship with a lawyer named Ray. “He is having one of those moments where he wonders if he knows me at all. It makes me want to talk, show him who I am. Or at the very least, what I want to be.” This is Sally at her most deranged. This is Sally rushing unnaturally toward a resolution that involves standing with Billy under the eye of a hurricane that just so happens to be named after Kathy. I was left desperately wanting to hear from Sally in 10 or 20 more years, wanting to hear the story from a Sally that’s lived long enough to discover who she is outside of Kathy’s shadow. There were more realizations to be had, more circumstances and truths to accept. I could imagine her story going on, this romantic ending just one of many possible endings.

Even here, I want to write his name like it will help you understand why I enjoyed one of these books and loved the other.

We always have room in our lives, even if it’s just an inch, to make a choice. This is something I emphasize each time I read Li’s “Extra” with my students, and it was at the forefront of my mind as I read Goose. Though Fabienne was the force of nature in their youth, it was Agnès who fled France and made another life that Fabienne could never touch. I’d done more or less the same to my Fabienne. Each time I saw him after I left for college I felt less like myself, and more like a child, and it was only in that story, of our childhood, that I could still find some familiar way of being with him. We had both changed until we no longer recognized each other; it was ultimately this, rather than any one betrayal, that I couldn’t handle. My Fabienne and I haven’t talked in months. Not a day goes by that I don’t think about him. Even here, I want to write his name like it will help you understand why I enjoyed one of these books and loved the other.

At the end of Goose, Agnès reaches a kind of acceptance. This is the end of the story. She’s followed her grief to its end, shining every possible light on it. Agnès’s memories of Fabienne felt more discriminating than Sally’s, the selection of scenes and details carefully cut out by Li’s master hand and hung on the page for the reader to encounter in all their carefully crafted radiance and mystery. Her act of remembering is less a reaching toward Fabienne than a reaching through, into herself. “I had heard her pain: there was something immense in her, bigger, sharper, more permanent, than the life we lived. She could neither find nor make a world to accommodate that immense being.”

I’ve done what Agnès does with my memories of my Fabienne. I started writing about him in college. We were already drifting apart, and he hated these stories, wouldn’t even talk to me about them, and I hated thinking he could’ve written better stories, if only he tried. Reading Goose, I had to keep reminding myself that he was still alive. That he might actually read the book I wrote to make sense of our story, a book that will soon come out into the world.

Sally, by the end of her story, is still talking to Kathy. And in a way, every time I write, I’m still trying to reach my Fabienne. To this end, Sally and I could both learn a thing or two from Agnès.

Advancing:

The Book of Goose

Match Commentary

with Rosecrans Baldwin, Meave Gallagher, and Alana Mohamed

Rosecrans Baldwin: I love how personal the judge went today. And can’t wait to read Hombrecito! Judgments like these are what makes this event so special to me after all these years of helping run it—to hear how a text meets a person and how they intermingle. As an author, it’s also one of my favorite parts of the job, my favorite part of book tours and events: to hear how a book found someone and what parts of them it reached.

Alana Mohamed: I liked that Judge Sanchez acknowledged how personally a book can touch you. In terms of the Tournament, though, I wish we had gotten more of their keen analysis. “The project of [Agnès’s] story isn’t to make the reader experience childhood and adolescence again, but to dramatize the process of trying to make sense of the past”—so good!

Meave Gallagher: Yeah, lotta vibes-based decisions this year.

Alana: I agree with their decision and admire them for laying out how they got there, though I don’t share their read on Notes on Your Sudden Disappearance. The tragedy of losing Kathy seems downplayed.

Rosecrans: Can you elaborate on that?

Meave: Yeah, I’ve seen some dismissals of Notes as, essentially, a gussied-up Nicholas Sparks novel, but I wouldn’t know.

Alana: I can see that! But Notes as a coming-of-age tale in Judge Sanchez’s terms—tracking linear progression, waiting for the process of self-actualization to take hold—would require an acceptance of Kathy’s death that Notes seems to resist. Sally is stuck in time, as if to say: I won’t accept this, I can never grow out of losing my sister. I bought that Kathy’s death could have such an impact, but not everyone did. It does make Sally’s closing-scene smooch with Billy-the-jock quite ominous, though.

Rosecrans: Let me take a step back. Do either of you write or read in a similar way to the judge here—trying to reach or remember (or keep alive) someone or the idea of them, or perhaps a period in your life, or a place?

Meave: I’m always wary to revisit media I loved before developing critical thinking skills; I fear being disappointed in and ashamed of… unfortunate elements I missed the first time. But in the spirit of Judge Sanchez, I’ll get personal. I reread A Tree Grows in Brooklyn after trying to watch The Automat—my husband cherishes his memories of visiting the Automat with his father, but we couldn’t finish the doc. “My father and his father were union men,” my husband said, “and this is erasing real fights for Automat workers’ rights.”

Alana: Talk about principle! We love a union man.

Meave: We do! Anyway, Automat reminded me of reading A Tree Grows in Brooklyn and romanticizing big cities and independence and the Automat, so, fearing the worst, I picked up a copy, and—it holds up! And it could be worse: I could’ve grown up idolizing Karl May’s Winnetou novels. Reading Holocaust histories for children was the better choice, right?

Alana: Are there any books you’ve encountered in adulthood that affected you in that way?

Rosecrans: I think I’ve mentioned this in previous Tournaments, but for me it’s rereading The End of the Affair by Graham Greene, one of my favorite books. I’ve probably read it six or seven times now, and the older I get, the experience gets darker—there’s just too much now that resonates on a personal level.

Meave: As I’ve said, The Book of Goose tapped into some deep feelings from my youth. I too miss my Fabiennes. Unlike Judge Sanchez, I’d rather not look directly at that pain again; Goose is a perfect intermediary.

Alana: Brown Girl, Brownstones by Paule Marshall did the same for me for its depiction of West Indian immigrants in New York and their hunger to own property. My dad gets emotional when he talks about owning his home, and it was a topic of importance in my family growing up. I was amazed to see some of those conversations depicted so accurately. As Martha Jane Nadell notes in this excellent paper (accessed through my local library!), Black West Indian immigrants have a complex relationship with racist housing policies and home ownership in America. There are parallels there to the Indo-Caribbean immigrant experience.

Meave: I respect that. Being ideologically opposed to land ownership doesn’t mean I’m ignorant of racist housing policies or class struggle. I’ll definitely read the Marshall.

Alana: It can certainly be seen as cringe to wax poetic about home ownership, which is probably why Brown Girl, Brownstones hit me so hard.

Meave: No judgment of you or your family or anyone who wants to own a home! I just wish we had alternatives that didn’t involve the WeWork guy with like nine houses telling us communal living = being your own super in an overpriced apartment building.

Alana: That said, I enjoy returning to the YA of my youth. A lot of the ones I remember feel like deep cuts—the types of books I had to check in with my inner librarian about. (Commentariat: Does anyone remember Witch of the Glens by Sally Watson or “Minnow” Vail by Winifred E. Wise?)

Meave: I sympathize. I swear I live with the only other person alive who’s read Esther Averill’s Cat Club books, whose main character is our cat Jenny Linsky’s namesake.

Alana: Ha! I did learn about those books from you. There is still a lot of beauty and nuance to my childhood favorites. Now, when I revisit one and can’t see myself in it, I feel admiration for the younger Alana who found ways to connect with stories that didn’t quite have her in mind.

Rosecrans: Love it. And now to the Commentariat, then join us here tomorrow for our second match in the semifinals, where The Rabbit Hutch meets Sea of Tranquility. Finals week of the 2023 ToB is going fast!

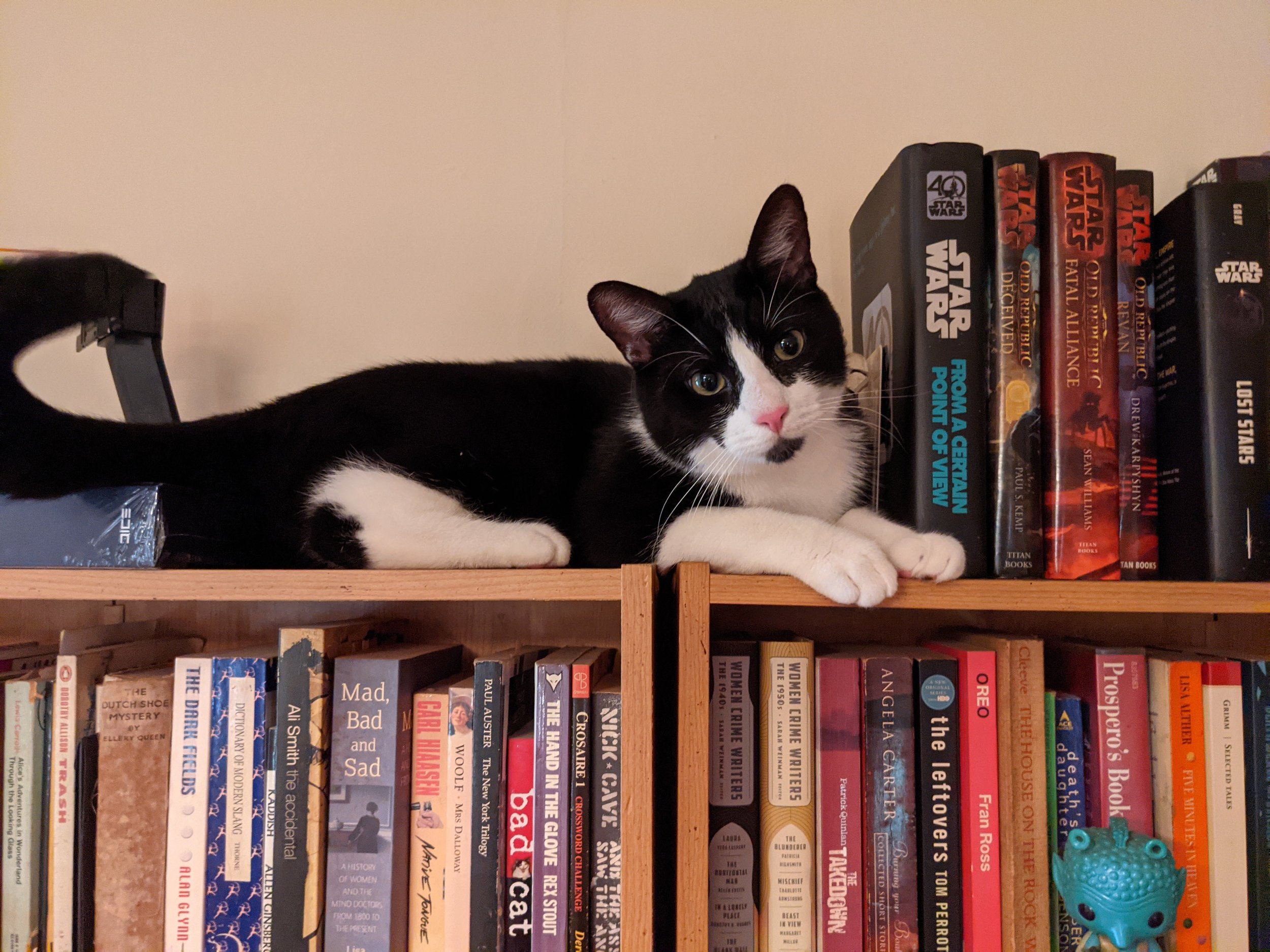

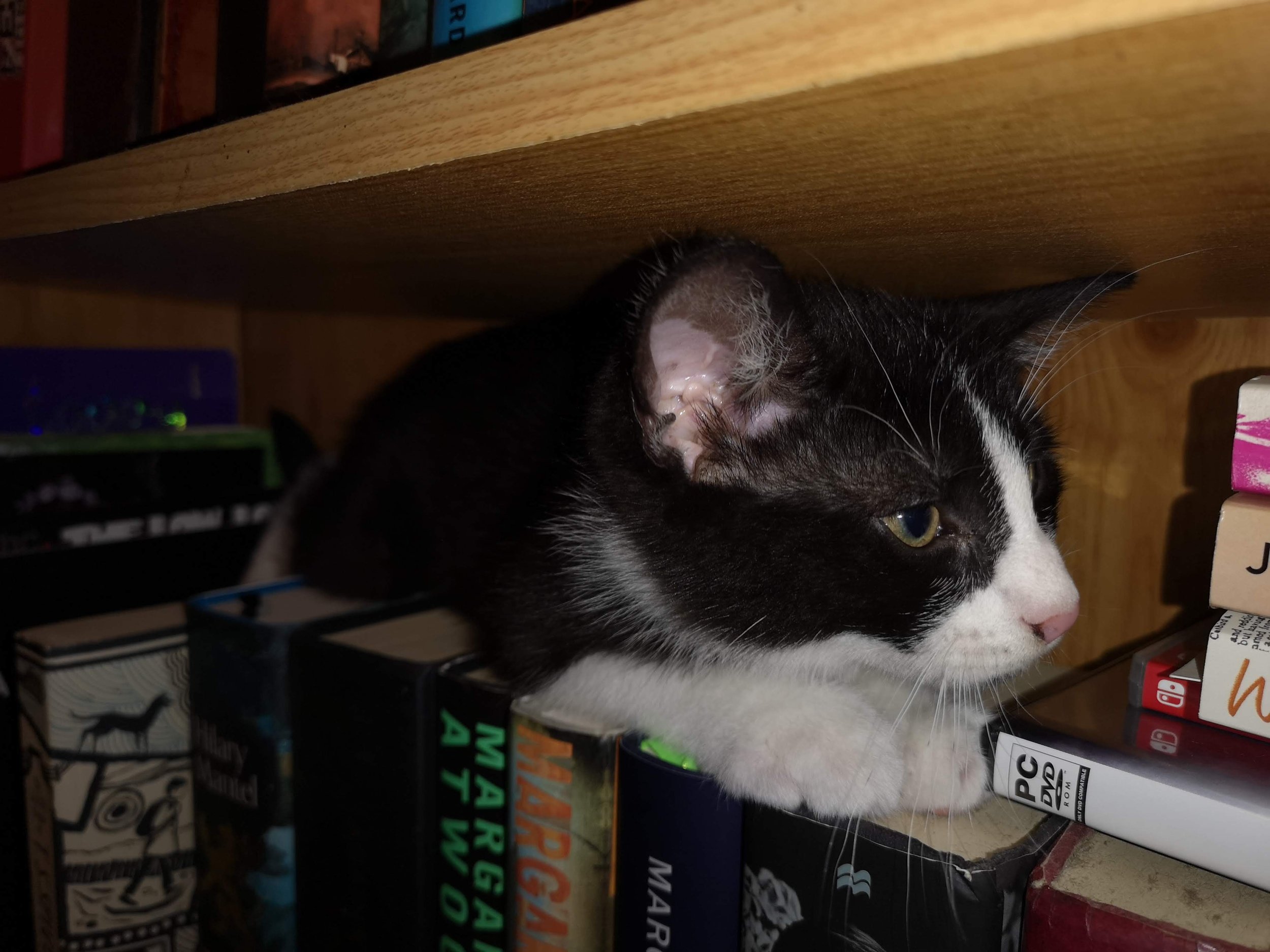

Today’s mascot

From Orla H., please welcome today’s mascot, the incredible Amos! Orla says Amos has been guardian of the bookshelves since he was a kitten. (He got too big to fit in there after a while, and it made him grumpy.) “I named him after Amos from The Expanse, but he's really more of a wannabe librarian,” Orla says. “He has strong opinions about how books should be shelved and since I don't understand his system he often has to remove books I've shelved incorrectly. He loves it when I read because it means he can curl up in my lap for hours.” We love Orla, obviously.

Welcome to the Commentariat

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus <spoiler> tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “<spoiler>Dumbledore dies.<spoiler>”

We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved” isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.